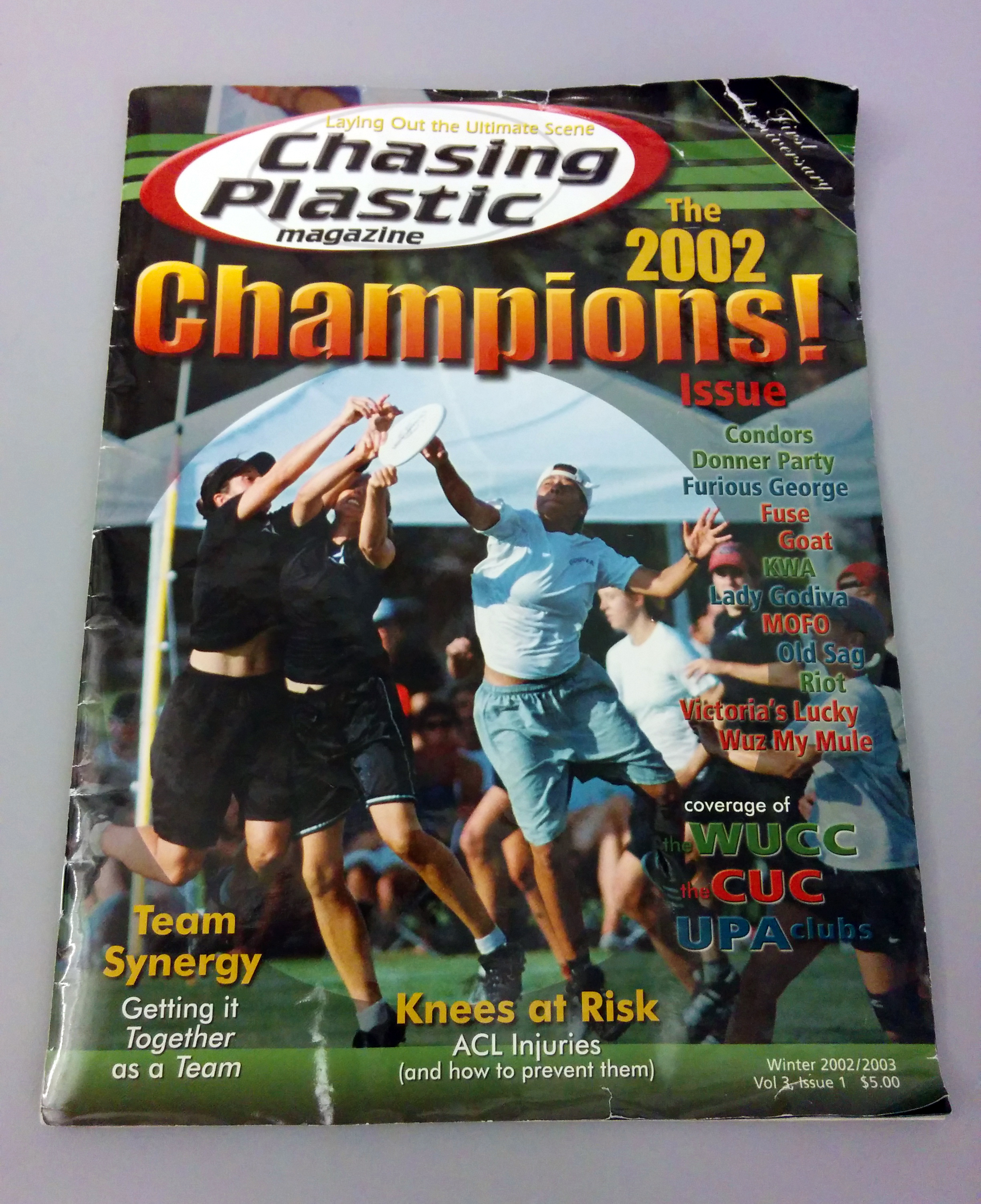

In the early 2000’s, ultimate’s first print magazine launched under the moniker Chasing Plastic. With the advent of digital cameras still on the horizon and active reporting websites nowhere to be found, Chasing Plastic brought photos and tournament recaps into the mailboxes of subscribers in over 10 countries. The magazine’s rise was almost as quick as its fall, however, and its story finds parallels in many great ultimate ventures. Eric Reder recently spoke with Skyd Magazine to share that story, presented below.

In 2000 I was living ultimate. I’d won back-to-back Canadian National Spirit Awards and a Canadian Championship, plus another appearance in the final. In the UPA Club Series, a Winnipeg-first qualification for Regionals was followed the next year by a close loss in the game-to-go to Nationals. Everything was ultimate. In the downtime, when the season finally ended and the snow in the north flew, I began to ponder how I could stay immersed in ultimate. I spent two weeks on a solo canoe trip into the wilds of Manitoba and came out garrulous, looking for a project, with a drive to test myself. Within a couple months, Chasing Plastic was born.

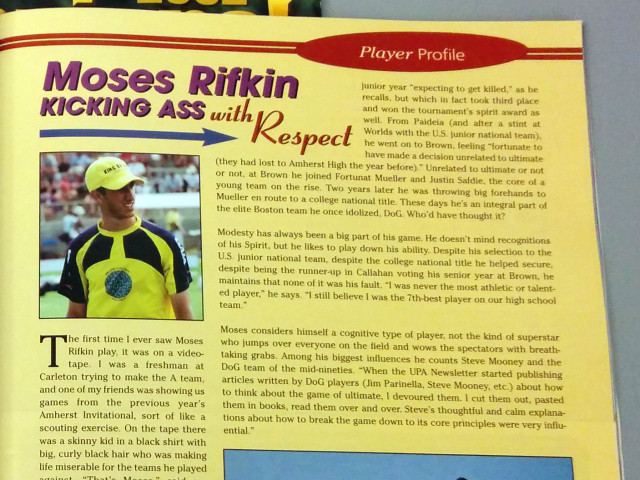

The magazine came from a desire to make something for the community, to impart the stories of life in ultimate through both words and photos. Ultimate players often try and explain the sport to civilians, with questionable results at best. When speaking to an ulti crowd, though, there is no need to explain how awesome the experiences can be. Chasing Plastic was about trying to share the wonders of the disc community with itself.

There had been an awakening of possibilities in that community by 2000. Videos of the UPA Club Series were being produced and sold. Companies were starting up to sell clothing for ultimate players. The market and interest had grown to a point where people were eager to see stories about ultimate outside of their own locale. League newsletters were not designed to express ultimate’s vibrant culture, though. Social media didn’t really exist yet, either. There were no online platforms to share video, nor was access as saturated or speedy as it has become. Digital cameras were not yet a functional reality.

This 2005 Canadian television video catches the magazine’s production in action:

It took work to share ultimate. Few people had the equipment and time to do it, and those technological limitations made the magazine a possibility. There was nothing around like Chasing Plastic, despite the growing interest from the community, so there was an opportunity to share in print the kind of content you would now find online. I was also in a position to develop that content, drawing on experience working as a snowboard photographer in Lake Louise Alberta. After moving back to Winnipeg I was already pulling my camera gear along to tourneys. Shooting film costs money, though, so part of the spark for Chasing Plastic was that it would make it possible to keep sharing those photos with the community.

I had also done some writing, and could draw on that. With no formal training and little practice, it was rookie writing–I had maybe a dozen articles published. Still, I felt the experience of working on editorial was enough to get started on my own magazine. A few other factors also aligned to make Chasing Plastic a possibility. A government program allowed me to collect some employment benefits as I took a business administration course, which meant I had an income to pay living expenses for six months while working on start-up for the magazine. I also set up shop in my dad’s basement–free rent always helps the bottom line.

Jason Savage and Scott “Big Daddy” Schinkel were my constant go-to’s for volunteer computer help, and I taught myself web design and digital editing with support from Duncan Hasker. For magazine layout–to me a foreign, specialized skill–I enlisted the volunteer help of a student at Winnipeg Technical College. He designed the first two issues for a class project while I learned Quark, and his design instructor supervised us both. Establishing the rest of the business was just like any other start-up.

There were two primary challenges to face as Chasing Plastic became a reality. First of all, I was a rookie publisher. Running a magazine involves a lot of different components. In the industry they call small magazine publishing a multivariant job, meaning I had to wear a lot of hats. Editorial, production, circulation, advertising sales and general administration all needed to be handled, and each department required its own systems. I started out with some camera gear and enough skill to use it, plus some writing experience, but everything else I had to learn as I went. Some things went smoothly, other things less so, and it all took time.

The second challenge was selling advertisement space. The ultimate community is not an ideal market for advertisers, so this was by far the toughest part of the whole enterprise. In order to justify their investment, companies want to see a local, specific, or sizable audience. It was difficult to explain the benefits of advertising to a comparatively small, diverse audience spread out across North America. Most companies were not interested in a magazine being distributed around the world, and it did not help that my magazine was a start-up.

“Chasing Plastic was never about selling ultimate players as a market for advertisers, though, and selling ad space was always difficult..”

Ultimate businesses, on the other hand, were excited about Chasing Plastic–but not convinced enough to write checks for advertising. They preferred to trade gear for ad space, which led to trying to sell merchandise through the magazine itself in order to balance the books for its production. When I took a course on Editorial Practice, a couple years later at Mags University, publisher after publisher talked about blurring the line between editorial and advertising in order to entice advertisers. Chasing Plastic was never about selling ultimate players as a market for advertisers, though, and selling ad space was always difficult.

Distributing the magazine, thankfully, was much easier. People get passionate about ultimate, so a full-color rag loaded with photos helped fuel and share the readers’ passion. Chasing Plastic was shipped to 10 countries, with the majority of issues going to the United States.

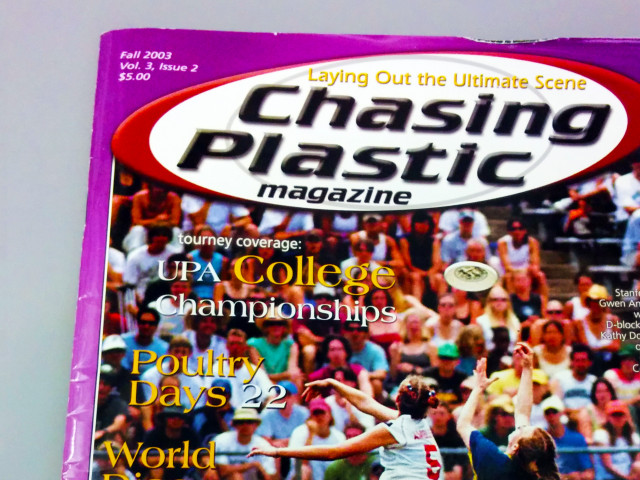

The vision was to get out on the field wherever possible to gather images and collect stories about life in ultimate. As the magazine came to life I’d get in my old Honda Accord and travel to major tournaments like Potlatch, Poultry Days, New Year Fest in Tempe, Fools Fest in Fredericksburg, Canadian Nationals, UPA Club Nationals and the College Championships. The routine would include playing a little, setting up a table with magazines, merchandise, and subscription forms, then shooting photos and networking with organizers and teams. Afterwards I’d head home to process film, scan and upload images to the website, work on ad sales and circulation or magazine production.

Eventually the road trips became more finely tuned, so boxes of merchandise, banners and camera gear all went in and out of the trunk fluidly every week or two. Reporting on competitive developments as teams trained for Nationals drew an interested readership, and tournament recap emails became part of the weekend work. I recall sitting in the car at 2 A.M. outside a closed Starbucks that hadn’t turned off its wifi, using the signal to upload photos and a blog post. Weekends were a whirlwind of tasks to be handled, but the load seemed less burdensome since it was all working with the ultimate community.

Outside of road trips, getting a balance of regional contributions was crucial to Chasing Plastic. It was important to demonstrate a broad perspective, but also important for marketing reasons to avoid making a regionally-exclusive product. Finding talented writers and photographers was challenging, though. There was little pay, and people with the requisite skills had a lot on their platters already. The difference between a photo shot with an f5.6 lens compared to an f2.8 lens is also big, which meant you were really looking for the few people who had good gear and the willingness to share their work. Digital was not yet the medium of choice for photogs, and getting anyone to shoot enough film to gather great shots was difficult, not to mention costly. Chasing Plastic was a business, so it was unfair to ask for people to work for free. You could only ask for what you could pay for. Scobel Wiggins was one of the people who really helped and supported the magazine, asking for little if anything in return.

With all the overhead, subscription income was just starting to pay for the magazine’s production costs by its third year. Unfortunately, Chasing Plastic was not selling enough advertising space to make it sustainable. In particular, merchandise received in return for ad space had to be resold, adding work that distracted from actual production tasks. In order to keep going, the magazine relied on a combination of small revenue streams (e.g. photo posters were sold to supplement cash flow).

“For myself I have no regrets. The ultimate community provides a life worth living…”

By 2003, though, there were signs that Chasing Plastic could not survive. Even with a frugal mindset, for the first few years the books showed a salary of just a few hundred dollars per month. Working late into the evening most nights eventually gave way to other obligations. After the second and then third trip seeking financing to continue, debt cast a shadow over the magazine’s future. When my father’s house was prepared for sale, the free rent was gone and the little extra money spent for office space downtown cut into the magazine’s cash flow. Realizing that I needed a part-time job just to pay the bills became the death knell for Chasing Plastic. Time spent working elsewhere was time not assembling an issue, time not selling merchandise or ad space. There was too much for a one-person operation to handle.

Some projects, even some with seemingly insurmountable challenges, you can try and will yourself into completing. It’s like the layout D you know you’re not getting, but you leave your feet for anyway. In ultimate you might make the cutter drop the disc, or make the thrower think twice before passing to your matchup the next time. If your layout bid fails, there are still some potential benefits. But when your business fails, when the cash flow can’t cover your costs and the bank demands payment for the debt, there aren’t any benefits for trying to continue. You cannot will your budget numbers.

With more start-up money, free from the burden of finance payments, the magazine may have reached a stable business model. There were plenty of subscribers hoping for more issues, but the money to print them didn’t exist. The rise of digital cameras and the increase of internet contributors within the ultimate community all coincided with the quiet fade of Chasing Plastic. The ultimate scene continued to grow with new avenues of communication online.

Watching a very public business fold under your guidance is hard. I’m also still paying off debt from the magazine, more than 10 years later, when houses my friends bought for about the same investment in 2000 have since doubled in value.

I don’t have a house to show for my investment. On the other hand, the depth of knowledge and experience I gained in producing the magazine work has led me to an incredibly rewarding multivariant job, directing a field office for a large national environmental group. Debts from the magazine are like a student loan, really. It all depends on your perspective.

I am also grateful for the years I spent immersed in ultimate, meeting the players and organizers behind development in cities across the continent, watching progress, triumph, euphoria, camaraderie, Spirit–and sharing those stories with the community. There is only one regret I have from Chasing Plastic: that the people who supported the magazine through subscriptions never got a chance to keep receiving issues. For myself I have no regrets. The ultimate community provides a life worth living, and I’m proud of the role Chasing Plastic had in sharing that with others.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.