The elite game began to settle down in 1995. Boston champion Death or Glory (DoG) led the charge in developing a superior strategic game, analyzing the ebb and flow of a typical game and applying rational techniques to go with the flow.

“Our offense was structured to ‘take what they give you,’” explained DoG strategist Jim Parinella. “If you wanted to take away our deep game, we would take a series of in-cuts up the line. If you fronted us, we would look to huck it on the first pass.”

By not forcing the action, DoG began to develop a much different perspective on controlling the temperament of a typical game.

“Ultimate was pretty ugly in the 1980s. It was OK to make a bad call and throw teams off their games. The greatest contribution DoG made to the game was to take that away,” said Paul Greff, a Michigan player with Night Train who moved to Boston in 1996.

Death or Glory rarely spiked the disc with venomous rage, talked trash or got wrapped up in a confrontation like their predecessors in the Club Open Division—yet they still won. It was a new style of elite ultimate.

Whereas the popular, high-yield four-person-play put the onus on the receiver to make the catch, Parinella and DoG preached patience and possession control with the responsibility on the thrower. Conventional wisdom suggested that victory required intense man-to-man defense, but DoG melded intense man-to-man with seemingly slack clam and zone sets. Aggression and focus were two pillars of success for elite teams, but DoG replaced these with reserved pontification and a smug, sometimes cavalier disposition. The Boston Brahmins were back and in charge.

The Dynasty Is Defined

In August 1995, defending UPA champions Death or Glory lost to San Francisco’s Double Happiness in the finals at the World Club Championships in Millfield, England. Two months later at Northeast Regionals, the bad boys on New York Cojones blew over Death or Glory like they were made of straw, winning 17-6. It looked like the new way wasn’t going to last long.

“1995 was a brutal year. We were terrible and there was a lot of bickering. None of us going into Nationals [Birmingham, Alabama] thought we’d be there at the end,” said Billy Rodriguez.

Instead, DoG turned it on at Nationals, winning all of their pool play games to earn a familiar semifinal match with their archrivals from New York. DoG’s thoughtfulness on offense wasn’t going to work against Cojones. Like the 1994 semifinal, the epic 1995 rematch had to be won or lost on emotions and personal vendettas.

In particular, there had always been a tremendous rivalry between the legendary Ken Dobyns and the great Boston players. There was no love lost when Dobyns’ knee problems resurfaced. “I remember that we knew that Kenny was vulnerable and we decided to exploit that. Three of our first six big hucks were over him,” recalled Chris “Cork” Corcoran, the team’s cocksure counterbalance to Cojones.

Boston’s surprising huck game gave them a half-time lead, 11-8. Cojones stole five of six to open the second half before Boston rallied to tie at 15s when a block by John “Bar” Axon provided a break. Two more of Boston’s deep hucks for goals followed and DoG went on to finals with a dynasty-defining win over their lifelong adversaries, 21-17.

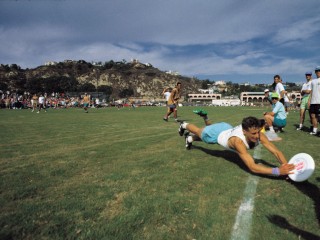

In the finals against upstart Seattle Sockeye, DoG showed that their defense defined perfection. Sockeye, from the newly created Northwest Region, had upset Double Happiness in semifinals behind the brash leadership of former New Yorker Jon Gewirtz and his implementation of the New York playbook. But Death or Glory’s defense devoured the familiar four-man play and the fish, winning, 21-10.

DoG committed only three turnovers in the finals; the defensive unit converted 11 possessions in 11 tries. Boston had set the high-water mark for the perfect ultimate game by relentlessly innovating on defense.

DoG’s use of the clam and a variety of shifting defenses had become a force unto itself. “Our clam relied on the fact that by switching defenders in the cutting lane, maintaining a strong mark and playing tight man-to-man on the handlers, we would leave one spot on the field hugely vulnerable to a completion—the cross-field blade or hammer—and leave two throws that looked appealing. But only because defenders were actually switching before the offensive player came in to the area,” explained defensive captain Billy Rodriguez. “When it worked really well, like the Seattle final, we could smell the fear.”

In the summer of 1996, DoG brought some attention to the new civility at the World Championships in Jönkoping, Sweden. Representing Team USA, DoG won the tournament and the Fair Play Trophy—the Worlds’ equivalent of the Spirit of the Game award. DoG’s success meant that teams seeking to be successful had to respect and emulate them.

By the fall of 1996, the Death or Glory legacy continued to grow while power squads in San Francisco and New York began to rebuild. The team added Paul Greff and Eric Zaslow to their Nationals’ roster and, more importantly, kept Steve “Moons” Mooney from retiring early.

“Steve was the leader. He was strong enough to keep this group of strong-willed people under one umbrella,” explained Greff.

Mooney’s 6’6” frame was imposing and his left-handed release gained him fame as a mark-breaking handler. However, it was Mooney’s will to win and dedication to the sport that made him a legendary leader of a legendary team.

“Moons was kind of one of my idols,” said rival Dennis “Cribber” Warsen. “You have to give him credit for his longevity. Moons was doing it for 20 years—20 years in a row.”

“Ultimate is an endurance sport and I’ve been involved in athletics my entire life except to eat, sleep and go to school,” Mooney said recently. “I’ve been organizing fun from the minute I can remember. I always thought a good time was less about getting the play right and more about everyone doing the same thing. It’s more fun if we’re all together and we’ll probably win if we’re on the same page.”

Mooney’s presence kept DoG’s core intact for another three seasons. Mooney, Parinella, Rodriguez, Alex de Frondeville, Jay “Bickford” Watson, Jordan Haskell, Lenny Engel and Michael Cooper all stayed with the team throughout their entire championship run.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.