“What I’m doing isn’t normal,” Michelle Ng realized. It hadn’t occurred to her until a high school baseball coach told her that he would never allow a girl on his team. Ng was one of the best pitchers in the league. Her strength and skill earned her teammates and coaches’ respect, but their support rarely carried over to other teams they played. Her opponents had never seen a girl play baseball, never been struck out by one either. So when Ng was hitting, they’d test her by pitching inside to back her off the plate. And on the stand, people were talking. “Looking back, I don’t know if that was a healthy environment,” Ng says. “It wasn’t like I had teammates to talk to. I certainly wasn’t going to go to them and say, ‘Hey guys, I really feel like these other teams are picking on me.’ I didn’t feel like that was the support I was going to get from them, or would want to get from them, because I didn’t want to be treated differently.”

Emily Baecher (Photo by Christina Schmidt – UltiPhotos.com)

Because of the physical differences between college aged men and women, Ng wouldn’t have been able to play Division I baseball. Her experience is evidence that women and men have bodies that move in different ways, as many have noted in response to recent surge of articles around gender in ultimate. And since we live in a society that values male bodies, we’ve been trained to view men’s sports as the gold standard. In Tiina Booth’s response to Emily Baecher’s reflection on her Boston Whitecaps tryout, Booth writes: “people with power do not willingly give it up to the group they consider The Other and it is naïve to think that ultimate is any different.” The comments that harangued Baecher’s article affirm that people are afraid of women gaining power in the ultimate community. And those who have ever matched up against a woman like Baecher or Ng know that there’s something to be afraid of.

After Ng enrolled at the University of California-Berkeley, she started looking for a new sport to fill her time. Ng missed ultimate tryouts at Berkeley, so she started out on the B team along with a number of other athletic, committed players. At sectionals, University of California-Davis bageled them 14-0. “It was devastating, and not because we lost – we didn’t expect to win – but because we all felt like we had no hope of competing at that level,” remembers Ng. “I thought if I could ever maybe go to college nationals that would be awesome.” From playing baseball, Ng knew what it meant to push herself athletically; she went on to captain Berkeley’s A team, and was a top three Callahan finisher in 2006.

Although Berkeley has successful men’s and women’s ultimate programs, Ng never considered playing open. “I’m not sure what transition happened in my mind,” she says, but it never felt like an option. Playing women’s ultimate revealed what had been absent from her baseball career: “For the first time, I remember feeling that connection to my teammates. Yeah, they were supportive like my teammates in high school were, but it was more than that. They were my closest friends. That aspect of community really drew me in.” Then, she moved to Texas.

Michelle Ng (Photo by Christina Schmidt – UltiPhotos.com)

Ng joined the University of Texas at Austin’s women’s team, Melee, while starting her Masters in Community and Regional Planning. She was stunned that there weren’t any national caliber women’s teams in driving distance. “We were lucky in Austin to have Showdown there, and they would do skill clinics. But the other teams in Texas didn’t have those resources. At Berkeley, we had resources in the program and were constantly playing against and learning from Davis, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, and there would be these exchanges of information and strategy.” Although there was a higher density of men’s teams in the south, the women’s division was nearly a decade behind what Ng saw in the Bay Area.

“We need to be the ones to create the change,” Ng then realized, “That is our responsibility.” As Ng spouted outlandish ideas – like flying to five tournaments a year – her teammates told her she was crazy. Then, they gave her ideas life. For example, Ng knew that Melee needed to play their regional competition. Apart from Centex, the best teams in the middle of the country weren’t coming to Texas, so Ng and her teammates hosted a tournament thirteen hours away in Columbia, Missouri. Ng planned the logistics remotely while writing her Masters thesis. “That tournament opened my eyes to what was possible, because I don’t think that’s the solution that many college students would choose if their team didn’t have options for tournaments.”

Ng believes that the college women’s scene is changing, even though the changes are incremental. Without Limits, the organization Ng co-founded in 2010 to strengthen the women’s ultimate community, has accelerated the change by hosting 60+ tournaments and skill clinics across the country. While Ng is proud of Without Limits’ success, she also knows that the work is never going to be over. “At some point, I’m not going to be able to do this anymore,” she reflects. Ng used to think that there would be a moment where college women’s ultimate would achieve equal access to the opportunities and resources available in the men’s division, but recently she has accepted that there will always be more growth to achieve in college women’s ultimate, more teams and players for her to support. This knowledge stems from her holistic vision: Ng is mindful of how she can boost both top college women’s teams and newer, less competitive squads.

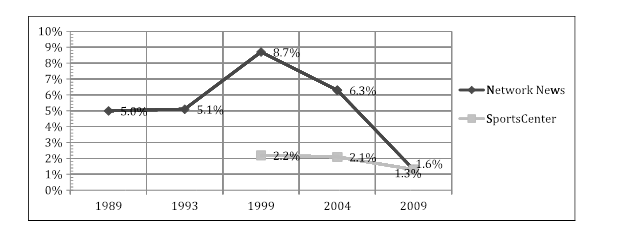

It’s not an accident that the ceiling and the floor are higher for men’s ultimate, or that men’s ultimate gets more press coverage. The disparity isn’t unique to ultimate, either. Sociologists Cheryl Cooky et al. make this clear in their article, “Women Play Sport, But Not on TV: A Longitudinal Study of Televised News Media.” From 1971 – 2009, high school girls’ participation in sports has grown from 294,000 to 3.1 million, as compared to high school boys’ increase from 3.7 million to 4.4 million athletes. College sports mirror this trend (Cooky 221). “However, during the past two decades of growth in women’s sports, the gap between TV news and highlights shows’ coverage of women’s and men’s sports has not narrowed, rather it has widened. Women’s sports in 2009 received only 1.3% of the coverage on TV news, and 1.3% on ESPN’s SportsCenter,” claim Cooky et al (210, 221, see Figure 1).

Figure 1: News and SportsCenter airtime devoted to women’s sports, 1989-2009

Cooky et al. also debunk the assumption that the media provides fans with men’s sports because it’s what audiences “want to see” (226). They discern that those who create programming targeted at men on programs like SportsCenter assume that “mostly male viewers want to think of women as sexual objects of desire, or perhaps as mothers, but not as powerful, competent, competitive athletes.” However, that assumption is in conflict with what audiences do, in fact, “want to see”; the University of Minnesota’s Tucker center found that athletically competent portrayals of women generate more interest in women’s sport than sexualized images of female athletes (223). The assumed heterosexual, cis-gendered male perspective of programs like SportsCenter marginalizes women and renders queer women and gender nonconforming athletes invisible (224). Furthermore, it keeps men’s sports in the spotlight of athletic and social life. Even though participation in women’s sports has tremendously increased, its lack of coverage tells audiences that sports “[continue] to be by, for, and about men” (205). These findings resonate in light of the recent conversation around the men’s professional ultimate leagues.

Can ultimate resist the incessant privileging of men’s sports, bodies, and voices? According to Joanna Neville, a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Florida, college women’s ultimate challenges patriarchy in key ways. Neville started playing ultimate with Florida Fuel in 2003; ultimate’s unique culture motivated her to conduct ethnographic research on how college women ultimate players negotiate gender. By studying how women ultimate players dress, speak, and move, she found that women athletes take on a masculine identity because a masculine identity is an athletic identity. “When you look at mainstream sports – the dominant sports like basketball or football or baseball – being an athlete in those spaces means being masculine. So being physically aggressive, being dominant, being powerful,” Neville describes. That also means using one’s body as a machine to win. “It hurts you, as an athlete in that setting, and also often your teammates because it’s about creating a hierarchy of power and dominance,” says Neville, whose study outlines how college women’s ultimate creates a space where people can be masculine and powerful without recreating the hierarchy of dominance.

Different from many mainstream sports, women’s ultimate shares the same rules and guidelines as mixed and open; it doesn’t require a smaller field or disc, for example. However, with the advent of the professional leagues, Neville notes that ultimate is adopting mainstream cultural norms. She supports USA Ultimate’s official statement that it will not recognize or endorse the American Ultimate Disc League or the Major Ultimate League at this time because of their failure to provide playing opportunities for women. According to Neville, “USA Ultimate’s stance is an important step in keeping the core of ultimate that allows for women to be successful at least in these smaller spaces.” And it’s not just women who benefit from gender equality, Neville points out. “If you think about these cultures, like NFL football and locker room bullying and those climates, they’re oppressive for men. It hurts them,” Neville says. What will it take to create an ultimate culture where being competitive isn’t at odds with respecting all bodies?

Amanda Kostic, captain of University of Washington’s Element, is living that question as a girls ultimate coach. Kostic is in her third year of coaching at Nathan Hale, the same team she played for in high school. She is intentional about her role as a woman coach on a girls team, and she really believes in her players. On the occasions that she does coach mixed teams, Kostic is careful not to let the boys steal the show; the girls lead drills and scrimmages, and they often have to throw the goal for it to count. Kostic is starting small and dreaming big. “I want something equally as successful as what the MLU has offered for men,” she says. “It’s frustrating to me that we’re moving somewhere different but at the same time we’re just standing still in women’s sports.”

Kostic was emphatic that Baecher’s article hit home. Ng agrees, echoing Baecher’s claim that if she suddenly had the athleticism to play for Ironside, she wouldn’t do it. “I’d rather elevate the level of coverage and respect for ultimate so that young females can dream of being amazing women’s ultimate players,” she says. “We have to swim against the stream a little bit. There are younger female players that need us.”

What else do young women ultimate players need? They need to know that their sport matters. They need to know that their skills are valued. They need to know that their bodies are powerful.

Works Cited:

Cooky, Cheryl, Michael A Messner, Robin H. Hextrum. “Women Play Sport, But Not on TV: A Longitudinal Study of Televised News Media.” Communication & Sport. 1:3 (2013) :203-230. Print.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.