1987’s Championship featured the highest scoring game in Nationals history and ultimately led to David’s banishment from playing in Washington DC.The following is an excerpt from Ultimate Glory: Frisbee, Obsession and My Wild Youth available now on Amazon.

The semis of Nationals in 1987 pitted Boston versus Chicago. And I do mean pitted. It was a long and brutal affair with Chicago winning 25-24, the longest game, in terms of points, in the history of Nationals.

There were plenty of turnovers in the game, but the last one was mine. No regrets, people like to say. That is one of the most bullshit clichés of all time. In a larger sense I get it. As the father of a daughter I adore, I wouldn’t want to change any part of a life that has led to her. But what about cleaning up a few messy details? I regret not making a better throw at that moment, in fact would put it in the top ten of my life’s regrets. I guess that’s better than regretting having committed murder, but it is a regret still.

After Chicago scored I sunk onto the field. We all did.

Someone came up to me, patted me on the back, and said something nice about how I had played. Someone else, a player I respected, said, “You were a god out there.”

Then added: “Until the end.”

I saw no reason to reply, possibly no reason to live. But then I looked up and saw what hung from the player’s hand. A cooler.

“Any chance I could have a beer?” I asked.

“Sure, man.”

It had been thirty-two days without drinking, part of my fitness regimen that fall, and the beer was cold and I gulped it down. I would like to say I savored it but that would be a lie. I savored it about the same way a dog savors its breakfast. I asked for another beer and he gave it to me and I sucked that down too. A few more people gathered around and someone broke out a bowl and I did a hit. And drank another beer. I would continue to drink and smoke over the next hour with a deep aggressiveness, fending off what was sure to be a dismal off-season.

The one coherent thing I remember doing was wandering over to my backpack and taking off my Barbarians. Inside my pack was a T-shirt that my old teammate Hones had given me for just this moment. I tore off my Titanic shirt and pulled on the one he had given me.

“Instant Asshole: Just Add Alcohol,” it said.

It’s only in retrospect that we see that particular moments are huge turning points in our lives. Had I completed that throw I might be telling a different sort of story right now. Rather than singing the tales of heroes, I might have been a hero myself. I could have been a God of the game, a purveyor of arete. But instead I was about to solidify my role as a clown-prince.

Eventually I wandered over to the stadium to watch the finals between New York and Chicago. Steve Mooney was the captain of our team, Titanic, and all season long, to his chagrin, I had bellowed my obnoxious cheer: “Titanic, Titanic, our dicks are gigantic!” The cheer was meant to offend people, of course, but also to register my rebellion against our stupid choice of team name. I looked down at the field, now reduced to merely watching the finals, a finals that we could have been in had I made a better throw.

I skulked through the stadium, taking a piss on the grass behind the stands. Then I had an idea. Some folks from the UPA (Ultimate Players Association) were broadcasting from up in the booth near the top of the stadium, and I headed unsteadily up the steps. Outside the booth, I gathered myself, feigning sobriety. Then I opened the door, and making sure not to slur, told those inside that I wanted to ask a trivia question. I believe the question was “What player who played on the original Titanic team had played on the original Boston Aerodisc?” and that I told them the answer was Lief Larson. They thanked me and said they would announce it and then I asked, innocently, if there was any chance I could ask the question myself. Then they did something that no UPA official would ever willingly do again. They handed me the microphone.

I grabbed hold of it and was soon bellowing.

“Titanic, Titanic,” I yelled into the mic. And then, in a rare moment of self-editing, as if worried about shocking the few children in the stadium, I continued “Our Johnsons are gigantic!”

A great roar went up.

The rest of the night was a blur. My girlfriend’s team, Lady Godiva, had lost in the finals to the Lady Condors, and a few of my teammates and I piled in the van with the Boston women and rode back to our hotel on the beach. I played the drums on the van’s roof and led the passengers in rousing renditions of bad seventies songs. We sang “Delta Dawn” and “I am Woman” and of course, my old standby, “Brandy.”

“The sailors say Brandy you’re a fine girl,” we howled.

The next thing I knew I was on the balcony of a room on the 20th floor of our hotel on the beach, swaying too close to the edge, and then one of my teammates, Turbo I think, was steadying me and leading me back into the room. Around midnight we all headed down to the ocean for skinny dipping. About a dozen of us stripped off our clothes and dove into the powerful waves. I swam far out, hoping to wash away the day. I body-surfed my way back in and must have blacked out, because what I know of the rest of the story comes from its re-tellings by Turbo and Jeff Williams.

They were walking up the shore, with their clothes back on, talking about the day’s tough loss. Then they saw something thrown up on shore, and walking toward it, found me lying naked and unconscious just above the surfline.

* * *

I didn’t play competitive ultimate the next year, taking time off to work on my novel. But in 1989 I returned and played with Titanic once again. Once again the year ended with a crash. Once again we lost in the semis. If what you cared most about was winning, only one team was happy at season’s end, just like our rival from New York, Kenny Dobyns, said, and during that time period the happy team was always his.

I had played well but it didn’t matter. Unlike the last semis I’d played in, this time I felt we had been beaten by a better team. And they didn’t just beat us, but beat us soundly. Which is not to say I was not upset. Once again, I had failed at the one thing I was a success at.

After the loss, it was almost obligatory for me to create some sort of scene. I had left my “Instant Asshole” shirt at home, but that didn’t stop me from drinking hard. A small group of us—Bobby Harding, Turbo, Jeff Williams, Tom Watson and a few others—threw a party of our own out on one of the outlier fields, refusing to watch the finals between New York and the San Francisco Tsunami. But gradually we got bored with ourselves and, perhaps sensing the juvenility of our self-ostracism, migrated over the stadium where the finals were being held. We were sitting off to the side of where most of the fans were, when I noticed something. This time the game wasn’t being announced from a booth but right on the grass beyond one of the endzones, where three UPA officials stood around the mic. A notion formed in my head, which I excitedly communicated to my small band of friends. I need to get my hands on the mic. What would I do then? They wanted to know. I would sing “We are the Champions” to the New York team, now well ahead and on their way to their second title. But how would I get the microphone? The UPA authorities, the “regulators” as we had begun to call them, knew what I had done the last time with my “Titanic, Titanic” cheer and they wouldn’t let me anywhere near it.

A plan was hatched. The endzone where the game was being announced was clearly not a defensible position. There were only three announcers around the mic, so I put together a small war party, made up of Bobby Harding, Turbo and Jeff Williams, and after a drunken Patton-like speech, convinced them to storm the microphone. Or thought I convinced them. Half way through my charge I looked back and found myself alone. I could have quit of course, called off my raid, but what was this if not a chance for another stupid, futile quest? So of course I charged ahead and tried to wrestle the microphone from the announcers on my own.

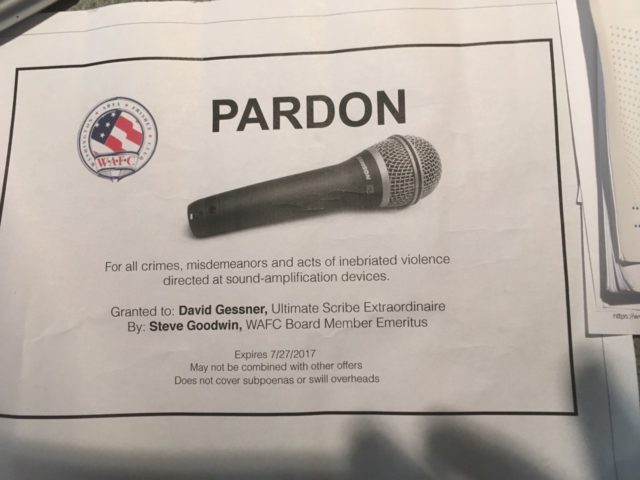

Three UPA officials and a policeman grabbed me and pulled me away. I was not arrested however. Things did not work like that in our Dungeons-and-Dragons world. Instead I was henceforth banished from ever playing Frisbee again in the Washington area, an edict which holds to this day. In the official letter that Steve Goodwin, the local representative of the UPA, sent to Steve Mooney, he charged Titanic three hundred dollars for damage done to the microphone. He also said that though he understood “that while Steve personally tried to help give ultimate a clean image,” this sort of behavior reflected poorly on the team.

Then he turned his ire on me. Referring to me by my last name–“I know him only as Gessner,” Goodwin wrote: “Gessner is now barred from participating in any WAFC sponsored event. I’m sure that this news will be greeted by him with howls of arrogant laughter, and you yourself might think that we’re being a little too serious. Let me assure you, we have never been more serious. There will be future UPA events in Washington, and it is more than likely that your team will qualify. WAFC will suspend all play at any tournament in which Gessner appears. His team will forfeit all games. Disappointed players will be told exactly why the tournament was cancelled. We’ll show them this letter.”

So there it was. Banishment, at least from play in our nation’s capital.

I wish I could say that I was properly chastised, that I began, then and there, to finally grow up, but I’m afraid the truth is I greeted his letter just as Mr. Goodwin had predicted I would. Over beers, I read the letter to some old teammates and we howled with arrogant laughter.

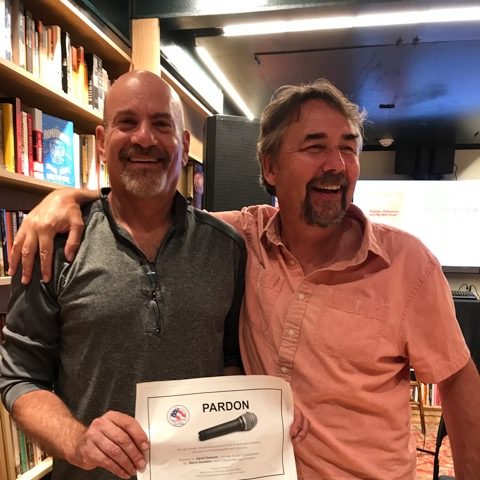

- David has since received an official pardon from Steve Goodwin.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.