Photo by Stephen Locke

Photo by Stephen Locke

I became hooked on ultimate during my postgraduate studies when I discovered that the sport was ideal as both a social and athletic space. In Edinburgh, Scotland, I found four incredibly social and active teams at the university and club levels (mixed and women’s). We travelled around the UK and as far as Italy to play at Burla, and my teammates became my closest friends and support system while across the Atlantic. I have always been a strong believer of the sport to be an ideal form of conflict management and engagement, and I could not play or champion the concept of spirit enough.

I was confused when I began to experience anger, frustration, choking anxiety and eventually panic attacks on the field, and found myself snapping at other players- both on my own teams and the opposing ones. At my worst, I responded poorly in particular to male pressure. During one high-stakes game, there was miscommunication between my male captain and I for the disc and he responded with frustration as we almost collided. The fear of potential collision combined with male pressure for performance resulted in my poorest show of sportsmanship I’ve ever displayed: expletives were articulated as I unlaced my cleats and stomped off the field, to only sit in my car alone and cry. To make matters worse- similar ‘snappy’ behaviour was mirrored in my personal life, which began to discount my hypothesis that I was experiencing these emotions due to a series of injuries. Each moment of anger or extreme emotion- quite often manifested as tears- was followed by severe feelings of shame, guilt and embarrassment. When I sought help, I learned that these were common symptoms of sexual assault trauma, which were further exasperated by two factors that originally made me fall in love with the sport: high-intensity competition and mixed-gender play.

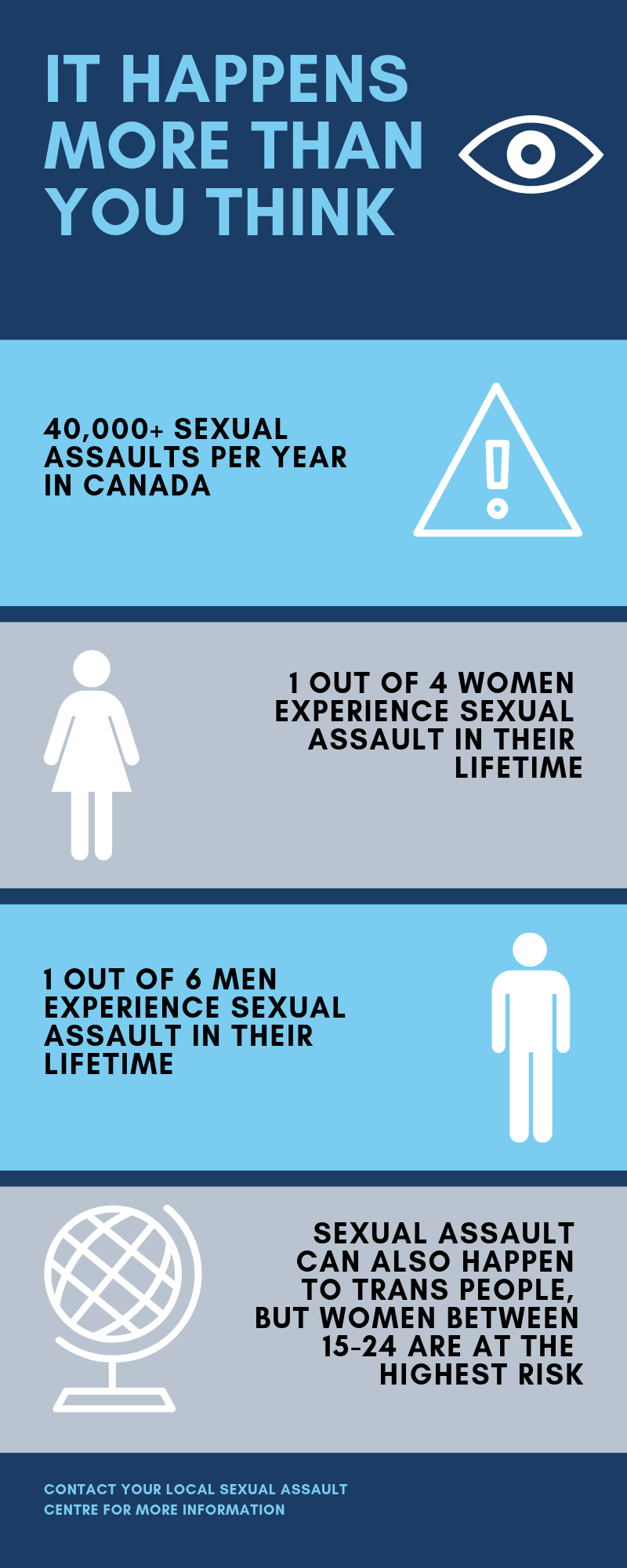

Sexual Assault is still highly stigmatized in society and can have minor to major effects on sport performance and sport membership. This article aims to highlight the effects of sexual assault on the player and on the team, and discuss ways for both the player and team to cope with ‘triggered’ moments on the field. Understanding, support and discussion about the effects of sexual assault on athletes is crucial to maintain a healthy and inclusive space within the sport of ultimate Frisbee.

The premise of this article was considered during a discussion coordinated by my local sexual assault centre (SAC). The SAC creates a safe space and guides discussion so that women (and men) can comfortably discuss their responses and triggers. It has been proven, according to the SAC, that understanding the chemical process of trauma aids the healing and allows you to develop coping mechanisms and strategies. For more information, please see your local sexual assault centre.

As an academic myself, I turned to research to support the authorship of this article and what I found was appallingly stark. There has been research completed on sexual assault in sports and performance anxiety around the performance of sports, yet nothing about the effects of sexual assault on athletes and their performance. This realization in itself was enough to highlight the importance of this article; even if it is an opinion piece based on information gathered about traumatic response, triggers and mechanisms.

What Is A ‘Trigger’?

First, the definition of ‘trigger’ is important: it is a sensory experience that sets off a memory tape or flashback that transports the individual back to the event of the original trauma and causes the individual to respond irrationally, with emotion, physical symptoms or thoughts. The brain cannot differentiate what happened then from what is going on at the time of being triggered. Symptoms of being triggered can include: fear, paranoia, anxiety and/or panic attacks, nausea/fatigue, irritability, hyper-vigilance, anger. Trauma can lead to physical symptoms, as much as mental, that manifest as muscle aches, headaches, high blood pressure and problems with blood sugar; it can also impact cardiovascular functioning and metabolic function. If an individual is taught to do so, there are ways to manage the triggers through grounding techniques.

Jim Hopper, teaching associate at Harvard Medical School, states that triggers implement fear responses from the defence circuitry, a collection of brain area that works together to defend against attacks and high-stress situations. When the attack is detected or stress is high, it can dominate the brain- impairing the rational prefrontal cortex- and shift behaviours to reflexes and habits. This is why one might fight, flee or freeze, similarly or differently to how she/he experienced the trauma.

While this can certainly be enough of a challenge on a day-to-day basis, one can imagine the difficulties of throwing oneself into a high-intensity, mixed-gender sport such as ultimate Frisbee; higher levels of stress and intensity result in increased triggering by victims. Playing mixed-gender also provides the extra risk of playing- and possibly coming into contact with- players of the opposite gender.

Mixed Ultimate Triggers & Coping

From my own experiences, my most difficult moments of playing ultimate Frisbee have been when a male player unexpectedly makes forceful contact (most often by accident) with me. The worst panic attack that I’ve ever had was when a male player hit me from behind and fell on me; this experience was incredibly triggering. I also started to get a reputation of being ‘angry’ on the field when I did not feel in control of the space and the security of my body. I stopped playing competitive ultimate for several months due to my insecurity around my responses to triggers and personal inability to discuss my issues with my team. Having returned slowly back to competitive play, I’ve developed a series of coping mechanisms:

1. Inform your team

This might sound like a basic consideration to most, but it is certainly the most challenging element for the player. An element of healing is required to even name your trauma, let alone discuss it with a group of people. If you are uncomfortable, speak to your captain and have him/her explain the generic elements to the team. I explain the triggering process and inform the team about my coping mechanisms (as seen below) so that everyone understands why I might respond irrationally out of the blue. For the teammates: be understanding and kind; don’t ask questions. Take what the player is explaining as face value, as she/he is talking about it to the best of her/his abilities.

2. Find what works for you, but separate yourself from the space

When I am triggered, I call injury or sub right away if it’s continuous play. It took me a long time to come to terms with this as an appropriate method, but the best thing to do is to remove oneself from the space and triggering environment. I was once asked by an opposing team why I called an injury after their male player hit into me from behind, and I responded (rightly or wrongly) with: ‘I’m not hurt, I’m just scared’ and my teammates took that as a sign to hustle me off the field. I have also in the past subbed, collected my things (irrationally, but apparently that made me feel safe), walked to the bathroom and then was able to rationalize myself out of the panic attack. Reach out to your local sexual assault centre or look online for appropriate grounding exercises. This response avoids a scene- as long as your team understands why you’re leaving- and allows you to return to the team with minimal feelings of shame and guilt.

3. Do NOT feel embarrassed and guilty

This is also an extremely challenging concept. The most common response after a triggering experience is shame and embarrassment. Teammates: this is your time to shine! Welcome the player back and encourage she/he back onto the field when she/he is ready.

Sexual Assault is still stigmatized, but an understanding of the effects on the brain and sport performance is necessary for all players to understand. This article is intended to be as much about how a trauma victim can cope within an athletic space as it is for teammates to understand what a player might be experiencing. Every response and every triggering experience is different, but can be aided by a supportive and trust-worthy team.

Today, I have happily returned to my local mixed competitive team and I continue to choose to play with teams that I trust wholeheartedly first and foremost. I still find myself using the coping strategies every once in awhile, but the triggering experiences are further and farther between. I believe that a better understanding of the effects of sexual assault trauma on ultimate frisbee- and sports in general- allow the community to create a safer space for players of all experiences and backgrounds.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.