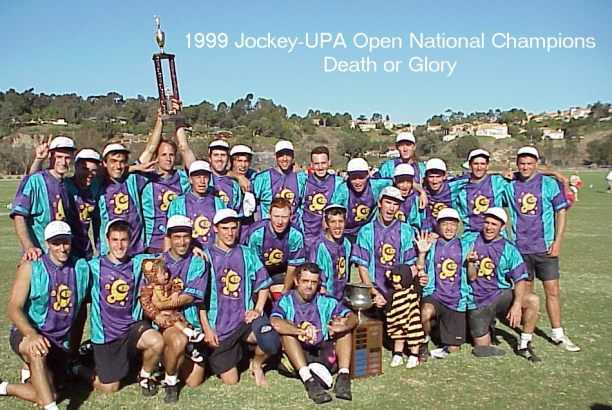

Author’s note: I used to write several articles a year for the UPA Newsletter. Two of my most favorite articles (“A Season on the Link”, Winter 1999, and “A Pound of Advice”, Winter 1998) were ones that took my DoG teammates’ words straight from their keyboards and gave the rest of the ultimate community an inside look at the team. For this article, I asked some old teammates and opponents for their perspectives.

Steve Mooney, Boston star 1981-2000: One of the ideas behind the name Death or Glory was that we’d lost for the last 12 years, and we felt that this was the year that we’d either win, or quit. Glory or Death. GOD! Death or Glory was close enough.

DoG was born in the spring of 1994 by a group of Bostonians who wanted to find an easier way to play the game. Or maybe it was created at the Mother’s Day tournament in Philadelphia in 1993 by an eight-man team who decided to play the Clam, a hybrid man-zone defense designed to thwart the opponent’s cuts from the stack, for the whole point instead of one pass. Or maybe it was a long, cruel birth after years of pushing, being pushed by, and losing to NYNY.

Mooney: I think that our fate was sealed at the Philly tournament that we won with 8 people. The theory was that we wouldn’t be able to win if we all ran for 6 games, so we made the decision to have one player score all goals in a given game. With that, our offense shifted from anarchy to pure focused determination. We won 6 championships on ‘The Man’, as we called it (though The Man did more than just score goals). We kind of did the same thing on D with what we called Junk D. We’d throw the disc out of bounds, walk down and set-up The Clam, and if they completed more that 3 or 4 passes, we’d essentially stop trying and walk back to receive the pull. These two things, The Man and Junk D, were huge factors in the formation of DoG and the birth of our championship run.

I think DoG’s #1 strength was our familiarity and trust in each other. This enabled us to simplify the offensive playbook and free our minds to be in the moment. Knowing each other’s strengths and tendencies meant that we could have different looks from the same formation without needing to specify what we would run—team-wide, we understood how to take what the defense gave us. We would huck it on the first pass, jam it up the line the whole way, or grind it out with a series of 5-10 yard comeback cuts, depending on what was available. The cutters would read the defense and take what was given, and the other cutters would read the initial reaction and fill in seamlessly. I should point out that we didn’t necessarily believe that this was the one true way to play, but that this style was optimized for our particular talents. We didn’t have any squirrelly handlers on the offense, for instance, so it didn’t make sense for us to have the handlers make a lot of attacking cuts, whereas our defense did have squirrels and so relied on the slashing handler cuts. The players were smart enough and versatile enough to be able to let the offense evolve. This implicit structure eventually became a weakness, however, as later DoG teams did not have the same cohesion but we still tried to fit the style to what had worked before.

On defense, our familiarity and experience allowed us to expand the playbook and still feel comfortable playing a variety of sets. Though our O line played exclusively “force forehand” after a turnover for many years, our D line mixed it up and tried to destroy the rhythm of the other team’s offense. Jeff Brown, defensive stalwart and strategist on DoG: I recently watched the video of the 1995 final, and Sockeye looked horrible. Impossible to know what they were doing downfield, but those guys hardly made it into the video. We played all our defenses in a beautiful sequence of man, Clam and 1-3-3 zone that had them guessing the entire time.

I came across Ted Munter’s wonderful article in the UPA Newsletter (“Playing with DoG”, Winter 2000; incidentally, this is the issue that introduces Will Deaver as “New staff” for the UPA) about what it was like to be a small part of the DoG dynasty, and he detailed a particular point in a 1998 Nationals pool play victory over the Condors. At double game point, Paul Greff got a game-saving block by reacting instantly to Bill Rodriguez telling him to drop in the zone to cover a pass that Rodriguez saw coming but Greff did not. There was that level of trust.

The downside of having such a veteran team was that it was much harder for newcomers to fit in and adapt. Ten of our original 19 stuck around for the entire championship run, which didn’t leave a lot of room for rookies . Nathan Wicks, DoG player 1999-2003, coach 2005-2006: Most of the team had been playing together for years, and not very many new guys had joined up…the team didn’t seem to have much experience welcoming players. As a tryout, I felt like an annoyance. Even after turning to Masters, where we added waves of new players every year, there was still a veteran core around which we tried to fit everybody. Without having practice, it was impossible for anyone to internalize what they should be doing. Occasionally we had enough of the old guard around and the offense flowed, but usually it was a struggle.

When I sent out my query to old friends asking them to contribute to this article, one common theme was how the teams benefited by rivalries. From 1992-1995,from spring tournaments with split squads to games with major titles at stake, Boston and New York would play each other 10 times a year. Jon Gewirtz, #1 enemy of Boston in his years with NYNY, Sockeye, and Furious: the Clam (Pre-DoG I know) really threw NY for a loop and we had to up our schematic game to beat it. Boston made us better, just as NY made Boston (DoG) better. Neither one of us would have achieved our runs without the other.

Mooney: The beauty of any sport is the rivalries. I can thank the Hostages for the Rude Boy win in 1982, and NYNY for the 6 between ’94-99. It was each of those rivalries that made us hungry, that pushed us to innovate. Later it became Sockeye, San Francisco, and Furious who kept us innovating and working hard.

Dave Blau, NYNY: Clam was precursor to all the lane clogging D we see today that forces many passes before the opportunity to put it deep. NY O was designed for 3,4, or sometimes 5 passes to score. And we did just that more often than not. Clam was designed to stop that and it did. The success of our O begat the junky D that’s seen today, and we really haven’t seen an O score in as routinely few passes since. That was a big contribution by DoG, and for sure, the NY O was the impetus. Everything connects.

The defining relationship with NYNY, even years after their demise, was a tough one. In their final championship year of 1993, we had a controversial loss to them in the World Club quarterfinals, and decided we needed to toughen up and remake ourselves even more in their image. I think we went overboard with our amped-up aggressiveness. We imploded against them in the semifinals of Nationals that fall after a melee brought on by too much chest-thumping after every goal. Yet another big loss, especially losing like that, left us disappointed and disillusioned. The team attitude had to change as we realized that we didn’t have to do everything NYNY did in order to win like NYNY. Two years prior, one of the Lady Godiva players told us that our problem was that we didn’t shut out opponents like NYNY did, so “Slugfest Bagel!” (Slugfest was a Sectionals-level team in the area) became the mantra. In 1994, we realized that this wasn’t really our personality. After all, those guys could get shot riding the subway to practice. We, on the other hand, practiced in leafy suburbs and drank craft beers afterward. Instead of trying to psych out our opponents, we tried to lull our opponents to sleep and then ratchet up the intensity at the end for a two-goal win. Beat them, but leave them feeling good about themselves and us.

Not everyone shared this sentiment. On his blog, Idris Nolan, who played with the strong Bay Area teams for years, once called us “the nicest cheaters in the game” (in fairness, he thought everyone was cheaters, but we were at least nice about it). Corey Sanford, longtime opponent with multiple NY teams and the Condors: The attitude I always felt from DoG was that despite everything you guys ever did, you never could escape the NYNY shadow. You had a big brother little brother thing going. You did things the same as NYNY, you did them different. You guys were the kid that was bullied for years and it left scars. And then instead of rising above that, you would always let it rear up at the worst moments. To me, one of the most quintessential DoG qualities was that to be the opposite of NY, you guys would try and play the Spirit card, but yet if there was ever a close game with you, that’s when the bullshit foul calls would come out. It’s like, be spirited or don’t. At least with NY people knew they were fucking assholes, and well, what were you gonna do? But you guys would play it one way and then switch it up when all of a sudden you might actually lose a game.

I respect what you guys achieved, both as a team and as individuals. But I think you guys could have done a little more to rise above what NY had done and you didn’t. And if that’s because you had to play for years against some guys who were just brutal, outright cheaters, well, who am I to judge?

Our final Nationals championship was over the Condors, but for some of us at least it was also a win over NYNY because it gave us six in a row, one more than their streak. It is thus only appropriate that DoG’s make-or-break game came against NYNY’s direct descendant, Cojones, in the 1994 semifinal. After a loss to them in pool play in the first tournament of the year, we beat them seven straight times, but needed everything we had to outlast them at Nationals. Winning that game transformed us into a new team, one that would win six straight national titles. How would that team have done against the vintage NYNY teams? I’m biased, of course, but I think that mental hurdle we cleared was enough that we would have been the favorites. Gewirtz: you could say that DoG played teams like an underachieving Double Happiness and an overachieving Seattle Sockeye instead of NY for its first 4 titles, but that wouldn’t tell the whole story. I honestly believe that the predecessors to DoG would have beaten DH and Sockeye (circa 95-97) as DoG did…. But against NY in 1993? Yes, the DoG of 1995-1997 wins, I’ll give you that, but not ‘92 or any other year.

Mooney: I don’t think that our 1994 team would have beaten NYNY. While we might have had the more talented team, they still had our number. However, once we established our confidence, DoG became unbeatable and would have won.

Another strength: we fought well together. Oh, sure, we hated each other at times, but it generally wasn’t personal. There would come a point late in the season where the O and the D were ripping at each other and practices were nasty and someone would throw a nutty. But once the adrenaline surge subsided, you’d nod and say to yourself, “Oh, yeah, we’re ready. Bring ‘em on.”

Of course, all the strategy and positive attitude in the world won’t win you games if the players are no good, and we definitely had some players who could play. Wicks: When I saw DoG from afar in 1994-1998, I felt like there were 3-4 HOF talents on both the O and D teams…there might have been 1 other team each year with that talent level, but that’s it. Odd as it seems, our 1994 shirts helped us to mesh all these talents without creating friction. “big ego ultiMatE”, they proclaimed. “Who’s the best player in the game? ME!”, the cheers went. We achieved our version of Revolver’s core value of Humility by acknowledging the existence of our egos so that others didn’t have to bow to them. We knew our teammates were good enough that none of us as individuals had to carry the team.

But Glory couldn’t last forever, as Death must eventually come. Just like losing to NY drove us, losing to us drove the Condors. They adopted some of our characteristics and tweaked them to make it work for them. Mooney: I know that Jim is a perfectionist and thinks that we could have won another 5 championships but I don’t agree. We maximized what we had. Other teams caught up to and passed us with their innovations. Just being “DoG” wasn’t enough. Wicks: I felt like the name DoG became as much of a burden as it was a benefit…the older guys had a sense of “these kids aren’t the guys I play with” and the young guys a bit of “so…where’s my ring?”

Greg Husak, Condors, also played with DoG Masters at Worlds in 2008: I think one of the things that started to wear on DoG was their reliance on specialized role players. There was a change in the landscape in the late 90’s and early 00’s, where the specialized player who could play wing in zone, or had great throws, but maybe wasn’t fast or athletic enough was getting phased out of the game. DoG’s innovative strategies maximized their role players and found places for many of them on the roster. But the emergence of the Condors, Furious George, Jam and others forced DoG to bring in some more athletic pieces, and in return they lost some of that institutional memory and strategic harmony. The result of this remade them from 6-time champions in a class of their own, to contenders who would have to battle on equal footing with the other contenders.

So it turns out that you cannot, in fact, win them all. But we had a good little run, and in this, the 20th anniversary of our creation and first title, we are staging some commemorative events, like a night out at the MLU’s Boston Whitecaps game on May 24. I feel lucky to have been part of the team, and proud to have helped shape it. To the 75 men who proudly wore the DoG uniform, I thank you for your commitment.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.