In the fall of 2016 I was a fresh-faced new captain of my beautiful team/family/best friends at Oberlin College. I had a buzzing head of ideas and a lot of ambition for the season — as well as a wide variety of other commitments. That fall it really started to sink in that along with being a full-time student working two jobs and a few other interests, my co-captain Jess and I were pretty much the sole people in charge of team of nearly 40 college ultimate players. As captains we planned and led practices four times a week, made cuts between the A and B team, and planned out and led the team at the season’s fall tournaments. Sometimes we succeeded. In other ways, we had pretty significant missteps. Looking back, I realize how badly we needed a coach at the start of our season, and can recognize significant improvements that the team was able to make once we acquired one in the spring.

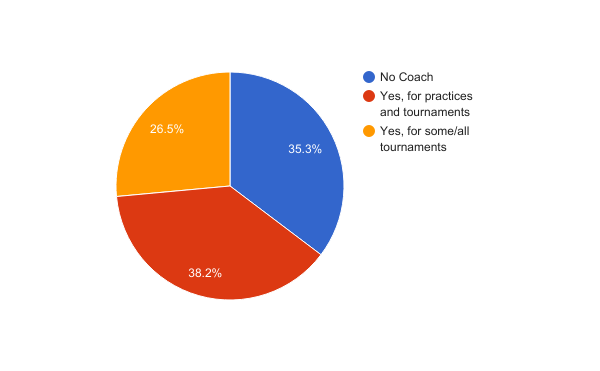

On so many other sports teams, having a coach is a given. How else would players in leadership roles develop themselves, as well as stay laser-focused during high-stress competition? This lack of coaching for a majority (if not all) of practices and at many tournaments is common to teams in Division III women’s ultimate. In a survey conducted by Ultiworld’s Marianna Heckendorn, it was found that out of 34 teams, 13 DIII women’s teams did not have a coach as a part of their program in the 2016 season. That’s 35.3% without, or more than 1 in 3 teams.

The numbers collected from this survey show that DIII women’s teams with coaches tended to be more successful. Out of the 16 teams that qualified for DIII Nationals in 2016, 12 (75%) qualifying teams had coach figures in some capacity during the year they played at Natties. Out of all of the responding teams that did not qualify, 11 out of 18 (61%) had coaches in any capacity.

The numbers collected from this survey show that DIII women’s teams with coaches tended to be more successful. Out of the 16 teams that qualified for DIII Nationals in 2016, 12 (75%) qualifying teams had coach figures in some capacity during the year they played at Natties. Out of all of the responding teams that did not qualify, 11 out of 18 (61%) had coaches in any capacity.

In the survey, a lot of teams noted that they had previously had a coach, but had trouble keeping them as a consistent part of their program. A member of Valparaiso responded that they had a coach two years ago, for one spring season. She noted that, “He was very helpful and we loved having an extra set of eyes as an outside perspective, but he moved away.”

Similarly, Emilie Willingham from Truman State responded that TSUnami had an alumna coaching them in Spring 2015 when TSUnami got 3rd at Nationals. Since then she had to move to Columbia, MO for work and is currently the coach of the Mizzou Women’s Ultimate Team.

Six other teams responded that they used to have coaches helping their team, but no longer do. It seems to be a trend that coaches move away from the typically smaller, more rural and more remote towns in which DIII schools are located. Willingham acknowledged that “TSUnami would welcome a qualified, skilled coach, but Kirksville is a small town and there are not many people like that.”

In contrast, Division I schools (of over 7,500 enrolled students) are typically in medium to large sized towns, and tend to have a larger surrounding ultimate community. A consistent coaching presence is largely a given for these teams. At the top level tournaments, it is commonplace for teams have multiple coaches on the sideline, sharing perspectives on strategy and serving different support roles for players.

Coaches are not the be-all end all for DIII Women’s ultimate teams — some teams really enjoy the freedom and take pride in being entirely independent. However, often the help of a more experienced, separate entity from the team can be invaluable, especially at tournaments and when managing multiple teams. Further, one of the hardest challenges of being a captain is finding the time for self-improvement when you are also in charge (and feel responsible) for team improvement.

Both the data collected here and anecdotes shared by teams seem to show that a greater prevalence of coaches would only serve to raise the level of competition and quality of place in the DIII Women’s division.

Finding Coaches

Acquiring a coach isn’t always easy. From my experience, here are some ways to connect and recruit experienced ultimate players to take on a coaching role in your Division III team:

Forging connections through alumni and nearby club teams may unearth some coach prospects. When current coaches move around and away, as they do, they should take the time to ask their ultimate friends and teams if anyone would be willing to replace them as a coach — even just infrequently or at tournaments.

Programs may need to provide financial incentives to get coaches to commit to long-term agreements to D-III college teams, as there is typically a lot of time and travel required to be a coach of a “way-out-there” small institution. Lobbying the club sports or activities leadership at your school for funding, can often be successful.

Many programs have ad-hoc money pools that simply expire at the end of the year — see if that can be utilized to help pay for your coach’s gas to big spring tournaments.

Don’t give up with the paperwork, even though it is bound to be bureaucratic. Instead, try to delegate the work and ask for help from sports department staff members. Further, crowdsourcing (especially your alumni) and traditional fundraisers are always ways to reimburse your coach that shouldn’t be overlooked. Paying your coach, even just a little bit, sends a clear message that their time is valuable and appreciated and may lead to higher retention rates.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.