Photo courtesy of Spin Ultimate

Photo courtesy of Spin Ultimate

The cutter runs deep. The huck is put up. All eyes are on the floating disc, and time seems to stop. Will the offense score? Will the defense take it all away? For most, there’s no greater feeling than a perfectly executed sky. Every team has that guy or girl who seem to come down with more of these than most. For some, it’s easier than for others, but the tactics involved in winning air battles can be learned.

I’m a Mechanical Engineer by education and trade with some exposure in biomechanics as well. I still have much to learn, but I have been studying the sky pretty closely ever since inventing the SkyLight. I have collected data at multiple professional combines, college tryouts, and big tournaments. For this article, I pulled out the SkyLight contest numbers I collected at the USAU College Championships earlier this year.

I usually collect three main elements: participant age, standing reach, and catching reach. From the last two I can calculate jumping vertical, giving 4 metrics to work with for some trend analysis. While this sample is fairly narrow, mainly including top college players (and some younger/older spectators), I did get 76 people to try it out and had the sunburn to prove it. Keep in mind that the techniques and measurements used for the SkyLight are much different than other vertical trainers. Players must catch the elevated disc with a running approach in order for it to count. While some may like to record standing-swatting verts, the SkyLight allows recording of a more natural and useful metric.

Data Disclaimer: This sample does not necessarily reflect the whole ultimate playing population’s gender, attributes or abilities.

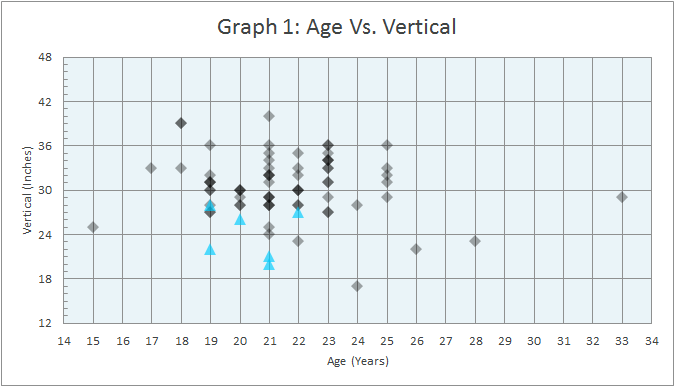

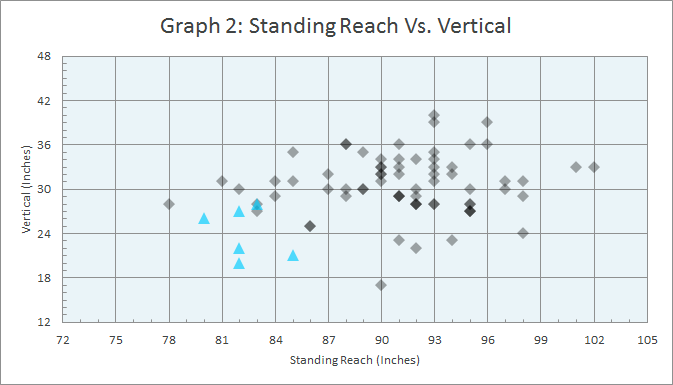

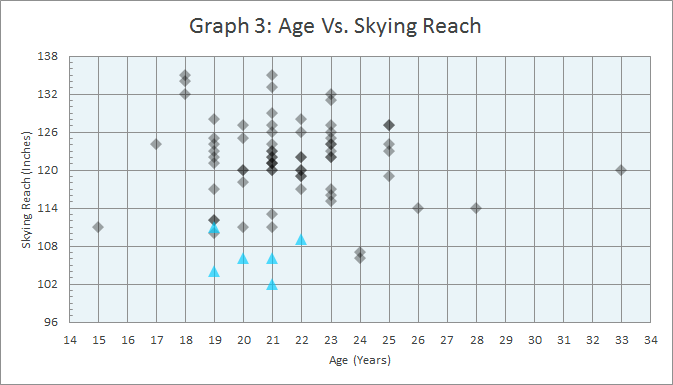

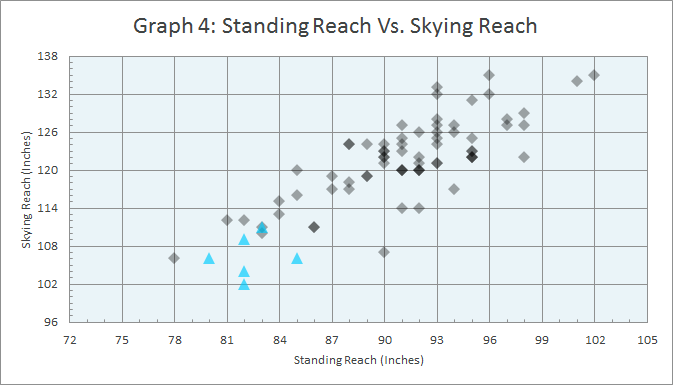

Key: diamonds = male, triangles = female, darkness shows data point overlap.

In the men’s college division (reduced to ages 18-23), this data illustrated an average skying reach of 10’ 2.5” and an average approach vertical of 31”. In the women’s college division, the averages were an 8’ 10” skying reach and 24” approach vertical, albeit with a limited sample size. Men do have higher averages, but women have higher potential than they realize. It is hoped that more women will be testing out their vertical so we have more data to better verify their benchmarks. For players looking to see if they have what it takes to win elite sky battles, these are benchmarks to consider.

What should players work on to improve their skills in the air? No matter where the SkyLight goes, players always ask for some tips on how to sky higher. In response to those requests over the years, I’ve developed a keen understanding that can help any personal situation. By employing these tips, I’ve seen athletes gain two inches in their vertical simply by tweaking technique. Along with some practice, training, and time, that vert gets even higher.

Opening Numbers

Players who want to improve their skying percentage should consider a few rough metrics to gauge their progress:

- Peak Percentage: How often you catching the disc at the highest part of your jump? Are you jumping too late or too early?

- Catch Percentage: How often are you coming down with the disc? Are you not getting a firm grip and missing your timing? Do defenders get in the way and you need to position your body better?

- Deeps Granted: How often are you thrown to deep? Are you cutting deep too often or does your team have a different plan in mind?

Know Your Tempo

To get the most height, you will want to have an approach with horizontal motion that can be partly converted into vertical motion. Depending on the situation, this may be running, jogging, or slowly boxing out. Even if you know where the disc will come into reach, you will want to time your pace to make sure you’re still in motion in preparation for your jump, rather than waiting right underneath it. This timing is also key for effective boxing out.

Disco Reach

There is a very common jumping technique that can deliver the most effective form and maximum height. By jumping off the opposite foot of your catching hand, you’ll be able to get that extra stretch at the torso between hip and shoulder. It’s the Pythagorean theorem: a2+b2=c2. The hypotenuse or diagonal on a right triangle is always longer than the width (hip to hip) and height (hip to shoulder). Be sure to time your last two steps extra carefully to grab the disc at the highest point you can, and avoid the up-early or double leg jump.

One-Two Step

Here’s why one leg jumps typically work better than two: Rather than seemingly doubling our mechanical power, we can actually be more effective at decreasing our motion resistance. By driving up the other leg (the side that we are catching with) with our jump, we can boost our momentum upward from all that leg mass. Our arms can perform the same task before they make the catch. Driving the arms from low to high toward a stretch can give players that extra inch alone. If you’re tall and lanky, try adding some spin to your jump to stay upright. With the centripetal force generated, it will minimize your tilt if someone unintentionally pushes your legs from under you.

Jazz Hands

You have a single moment at your maximum height, so your hands have to be quick. If you’ve come up from the arm drive, your arm should be fully extended toward the target with your hand in claw form ready to receive. As soon as that hand feels the disc enter, it’s time to lock a grip and pull it down to your side or behind you. Leave your hand up there with the disc and you never know what defender is going to slam your hand for a strip they claim was a D. As soon as you can stop the spin, take the disc out of contest all together. For defensive grabs, this is still important, but you can swat it down as long as it hits the ground rapidly. Avoid brushing and tips as much as possible to make sure your opponent doesn’t come down with a MACed disc.

The Finale

Here’s where just a little careful thought can go the distance in prolonging your playing career. Just as we used our leg to spring up, we will use both to damper and spring down. Feet and ankles are the first to cushion the fall, which are helpful to have extended rather than flat to start the deceleration upon contact with the ground.

Next up are knees. Knees should never be locked out when landing on a jump.This will not cushion the blow, but rather cause serious anatomical consequences. Most knee assemblies can only withstand up to 12 lbs of pressure when in the locked position.

From the bend in the knees then comes the adjustment in the hips to keep the torso upright and balanced. If you have weak hips or stability muscles you might find yourself falling over often. The end result at maximum compression should look something like a squat, which we can gently come up from. Make sure the hamstrings are not hypercontracting at the knee, as this can cause another form of injury than landing at hyperextension.

It is important to remember that each player is a unique mix of levers and motion capability. There are still some players who have restriction of movement problems from weightlifting or are dealing with a higher weight-power ratio. However, implementing a few of these tips can have a great effect on players struggling with certain limitations in their jump. As we continue to collect data, we hope to optimize player techniques wherever a SkyLight shows up.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.