The following piece is from Ultimate: The First Four Decades, available now in ebook form.

“I think we understood that the beauty was to keep the Frisbee moving and that that’s what it was about.” – Jared Kass

In the summer of 1968, Joel Silver, a willful, talkative, highly intelligent teenager from South Orange, New Jersey, attended a summer program at the Mount Hermon School, a boarding school in Western Massachusetts (now known as the Northfield Mount Hermon School). More than a camp, it was an educational enrichment program for college-bound high school students.

There, Jared Kass, a 21-year-old Amherst College student working as a creative writing teaching fellow and a dormitory adviser, along with other student-teachers, exposed Silver to a still-evolving game played with a plastic disc. By that time, Frisbees, sometimes known as Pluto Platters, had become fairly common in American homes, with the Wham-O Manufacturing Company producing a variety of models, including the Professional model, introduced in 1964 as the first “high tech” model for the serious player, and the Master model.

Even before the summer of 1968, before the invention of the plastic Frisbee, people were playing games with flying discs. In The Complete Book of Frisbee, Victor Malafronte documented how students at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, used a large size Ovenex cake pan to play a “two-hand touch” early version of Frisbee football as early as 1942. The game was created by brothers Bud and Tom Southard and dubbed “Aceball.” By 1950, one of the games was photographed for Life magazine by Elliot Elisofon.

Even before the summer of 1968, before the invention of the plastic Frisbee, people were playing games with flying discs. In The Complete Book of Frisbee, Victor Malafronte documented how students at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, used a large size Ovenex cake pan to play a “two-hand touch” early version of Frisbee football as early as 1942. The game was created by brothers Bud and Tom Southard and dubbed “Aceball.” By 1950, one of the games was photographed for Life magazine by Elliot Elisofon.

Malafronte also found evidence of another flying disc game that had cropped up at Amherst College circa 1949. It was related to Professor George “Frisbie” Whicher and involved throwing and catching “a plastic or metal serving tray.”

“In a letter to the editor, published in the January 1958 Amherst Alumni News, Peter Schrag (Class of ’53) describes this game, stating, ‘Rules have sprung up and although they vary, the game as now played is something like touch [football], each team trying to score goals by passing the tray downfield. There are interceptions and I believe passing is unlimited. Thus, a man may throw the Frisbee to a receiver who passes it to still another man. The opponents try to take over either by blocking the tray or intercepting it.’”

A decade later, Kass and his friends at Amherst—Bob Fein, Richard Jacobson, Robert Marblestone, Steve Ward, Fred Hoxie, Gordon Murray and others—began playing a version of Frisbee football with a plastic disc.

Willie Herndon, a math teacher, filmmaker and Ultimate player from St. Louis who fell in love with the game while a student at the University of Pennsylvania in the late 1970s, conducted a videotaped interview with Silver in 1997 that has proven invaluable in understanding the history of this period. During this interview, Silver mentioned Kass’ role, prompting Herndon to follow up with an interview with Kass in 2003—before plans for this book were developed. Both men were subsequently interviewed again on numerous occasions for this book.

During the initial interview with Herndon, Kass explained how this early Frisbee game came about.

“When I arrived at Amherst College in 1965, it was a very poor social environment, and not just in the sense of being an all-male school, but also in the sense that it was a fairly competitive environment,” Kass told Herndon. “We were trying to figure out how to be friends at the same time as knowing that you’re in a hothouse, an academically competitive environment.

“There were a bunch of us who knew how to throw the Frisbee and we also played touch football….I think that it was probably really in our junior year (1967-68) that it kind of happened and jelled—when we shifted from sometimes playing touch football or sometimes kicking a soccer ball around to using the Frisbee in that way. There was a moment when we began to play a team game using a Frisbee.”

Kass and his friends liked the Frisbee game because it was both fluid and fun.

“We spent a fair amount of time throwing Frisbees around and wound up playing what we called ‘Frisbee football,’” Fein recalled. “One could not run with the Frisbee. One tried to throw it to teammates with the idea of getting it caught beyond the goal markers. The defending team could not strike the Frisbee holder but could race to knock down or catch a thrown Frisbee. If the pass was incomplete, the defender got the Frisbee where it fell.”

Added Kass: “I think we understood that the beauty was to keep the Frisbee moving and that that’s what it was about. If you were running with it, then how could somebody stop you? It had to become a contact sport. So [we decided] it was okay to take a couple of steps to position yourself, but basically you couldn’t travel by running.”

The group often played anywhere from five to seven people per side, in a variety of locations on campus. They also played “to a set number of points,” Kass said. As with other pick-up games, “there were no referees,” Jacobson added. “We relied on self-regulation. But no one was taking anything very seriously so there was little need to call infractions. There were few rules, only common sense and a spirit of fair play were needed.”

Sometimes the games would even feature impromptu debate and discussion between plays, recalled Jacobson.

“Are you sure that you didn’t advance beyond where you caught the Frisbee?”

“Didn’t Shakespeare address that point?”

“What would Proust have thought?”

One day while playing Frisbee on the green of the Webster circle behind Amherst’s Frost Library (he is not certain precisely when), Kass had an epiphany. It was the same epiphany he would enjoy later in life while doing other things, such as singing Jewish prayers. But on this particular day, it came while he was running for the Frisbee toward a shimmering set of trees that served as the goal line.

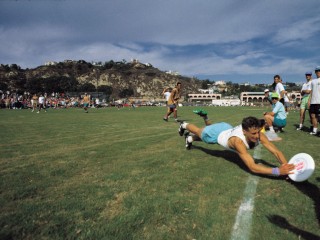

“I remember one time running for a pass and leaping up in the air and feeling the Frisbee making it into my hand and feeling the perfect synchrony and the joy of the moment, and as I landed I said to myself, ’This is the ultimate game. This is the ultimate game.’”

That was it. He just uttered it once, to himself. His friends don’t even recall hearing him use the word “ultimate” in association with Frisbee.

In the summer of 1968, Kass, along with several other student teachers at Mount Hermon, including Andrew Cohen, Peter Hayward, Jeff Jerbert and Steve Schneebaum, continued to experiment with the Frisbee game.

“A bunch of us got together and made up this game. I don’t remember any one person saying ‘These are the rules.’ It was a collaborative process.”

Hayward and Kass were in charge of the same hallway of students in Mount Hermon’s Crossley Dorm.

“As I got to know the guys on the floor, I could see that they didn’t have any good ways of relating to each other, besides listening to music…and drug-related activities that I was not supposed to know about,” Kass recalled. “They were a good bunch of friendly, high-energy young men, but they didn’t know what to do with themselves. Many of them clearly came from highly competitive environments. Some had already developed an abrasive, competitive edge. Some seemed lonely. Some seemed bored. Getting them involved in a sport seemed like a good thing to do. But in my gut I knew that the game should not be overly competitive. It should simply be fun—and I knew just the game.”

In an unofficial catalogue produced that summer by the Mount Hermon students, a lighthearted description of the Frisbee events appears under the heading “Recreational Activities.” “Four afternoons a week, all students participate in a program of supervised recreational athletics including frisbee, touch frisbee, tackle frisbee, water frisbee, one-handed frisbee, one-legged frisbee, three-legged frisbee, frisbee basketball, frisbee roulette and strip frisbee,” it read.

“Someone would drop a pass,” Kass said. “I could see the kid getting really pissed at himself, and I’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. That’s what’s cool about this game because the mistakes are what allow the direction to change so fast.’ And so it began to give them a way to relax. Sometimes somebody would take too many steps, and someone would start yelling, ‘You took too many steps,’ and I’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s right, but the most important thing is actually to keep the game going. So let’s not count steps, guys. Let’s try to just sort of self-regulate on this. Nobody’s gonna give you any trouble…”

Even though Kass and the others taught the nascent game with passion and a teacher’s eye for inclusion and teamwork, it is possible that it might have died on the vine had it not been for Silver’s presence at Mount Hermon. That fall, Kass returned to Amherst for his senior year, eventually moving on to graduate studies in psychology and higher education. He never pursued Frisbee seriously.

Ironically, it seems possible that his contribution might have been lost to history had Silver not mentioned him during his initial interview with Herndon.

Ultimate: The First Four Decades is available now for purchase on Google Books.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.