I believe there are key topics missing in the Step Up and Step Out discussion about gender equity. This project is lead by Rise Up and Sockeye’s Mario O’Brien and sponsored by Upwind Ultimate. The project focuses on men in ultimate who are determined to take a larger role and carry a heavier load in the discussion of gender equity in ultimate. They discuss ways to do this (and reasons why) through video conference calls.

SU and SO lined up very well-known players like Dylan Freechild and Jimmy Pickle to target a young male fan base, while they have live conversations addressing the possibility of a mixed AUDL, how men should be using social media in the gender equity movement, and other topics surrounding equity in ultimate.

While I appreciate Mario O’Brien’s approach to encouraging men to start taking a larger role in the discussion, I think the foundation for men’s engagement in gender equity is almost non-existent. We are jumping to support women in our sport –to hold them up on our shoulders and strengthen their voice– without realizing we don’t actually have the strength to hold them up.

Before we leap to talking about a mixed AUDL, how we can better support women’s club teams, or what men’s roles in social media should look like, I’m calling on the men of SUSO to discuss the basics first. I’m not an expert on this topic, but I have personally listened, learned, read, and written about these topics before. It’s my hope that by providing these topics for discussion, the SUSO group and readers will consider how they relate to them.

How do we (men) become more emotionally intelligent?

Women and men both deserve more emotionally intelligent men. Currently, women unfairly take on the burden of men’s emotions. Why? Because aside from anger and happiness, we’ve been socialized to believe that emotions make us weak and we shouldn’t show them to another man. So we view men who understand and can make space for emotions —which we only allow women to do— as weak or inferior. Until we accept emotional intelligence as a necessary strength in men, we will continue to see it as a weakness in women, no matter how much we say we respect female athletes. Later in the article, I explain why emotional intelligence should be a foundational building block for men.

What does it look like when men are vulnerable with other men on an ultimate team?

Again connecting this to gender equity in ultimate lies in viewing emotional intelligence and our ability to be vulnerable with other men as a strength. We can’t practice supporting a peer’s vulnerability without having some emotional intelligence and we can’t practice emotional intelligence with each other without showing vulnerability. On a team level, we may need to create rules and boundaries to make sure the space is safe to feel vulnerable in, while on an individual level relationships and trust may be targeted for improvement.

What steps can we take to unpack our masculinity?

Having a conversation about masculinity is an opportunity to identify our more harmful masculine traits and learn to accept our more feminine qualities. A culture of toxic masculinity oppresses feminine qualities in women and in men. How do we expect to accept and empower those same qualities in women, if we can’t even accept them in ourselves?

How do we develop a stronger sense and understanding of empathy?

Whether you are deeply involved in gender equity, supporting from the sidelines, or still wrestling with your role and how this topic relates to you, a developed sense of empathy is key to lending successful support. We can play a larger, stronger role when we walk through challenges, suffering, and discomfort alongside women in our sport, rather than express sympathy towards them. This will also help us create cultures of mutuality and collaboration instead of creating victims and saviors. Teams would benefit from mutuality and collaboration by balancing power dynamics among peers and strengthening communication skills. Power dynamics would balance out when teams are planning and making decisions not only with the consent of the smaller voices on the team, but those voices are being included in the process to collaborate meeting mutual wants and needs. This culture of inclusiveness would naturally strengthen a team’s communication skills as more people are being involved in directing the team.

Where do we fit in the spectrum of gender-based violence? What does the spectrum look like?

I suspect a lot of these topics would make most young men playing our sport cringe because I definitely would have as a twenty-something. But let’s talk about it anyway!

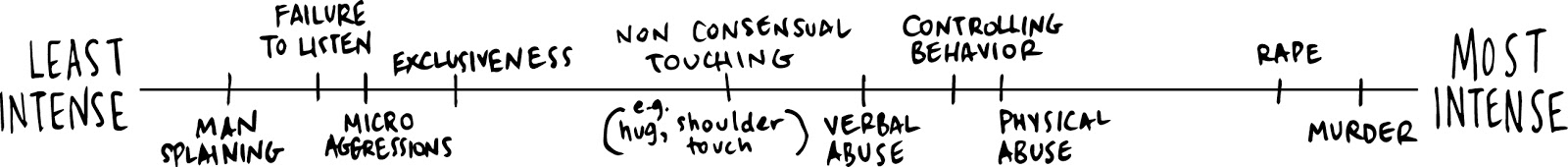

First, let’s get an idea of what the spectrum of gender-based violence looks like. From my experience, the far end of the spectrum (on the right), being the most intense violence would have rape followed by murder. Somewhere in the middle of the spectrum would be verbal abuse, physical abuse, and controlling behavior. At the very beginning (on the left), the least intense, would be microaggressions, exclusiveness, and failure to listen. I think everyone’s own experiences may shape this spectrum differently than what I’ve listed, which is valid.

Illustration by Bailey Zahniser

Again, from my own experience, the majority of men’s team cultures and behavior falls on the lower intensity side, with microaggressions, exclusiveness, and failure to listen. I would hope the majority of us don’t fall on the other side of the spectrum, but there have been cases in our own ultimate community of men’s behavior reaching that far right side. Objectifying and oppressing women with behavior on the left side normalizes the behavior on the right side. It’s important to know where you personally are and where you’ve been on this spectrum to know what negative contributions you are making or have made in the past towards women’s safety and equality before you ask others to make changes around this behavior.

What does accountability to the above look like?

To hold ourselves accountable for where we are on the gender-based violence spectrum we have to figure out why we are there and what needs we are trying to fulfill by behaving the way we are. As a team are we using microaggressions because we actually believe women and their bodies are inferior? Or are we struggling to communicate when we witness weakness and vulnerability in our peers?

***

I’m not saying that the current Step Up and Step Out topics aren’t relevant or shouldn’t be discussed, but I think they need to be discussed after we’ve developed a stronger, less fragile, and more balanced masculine team culture model.

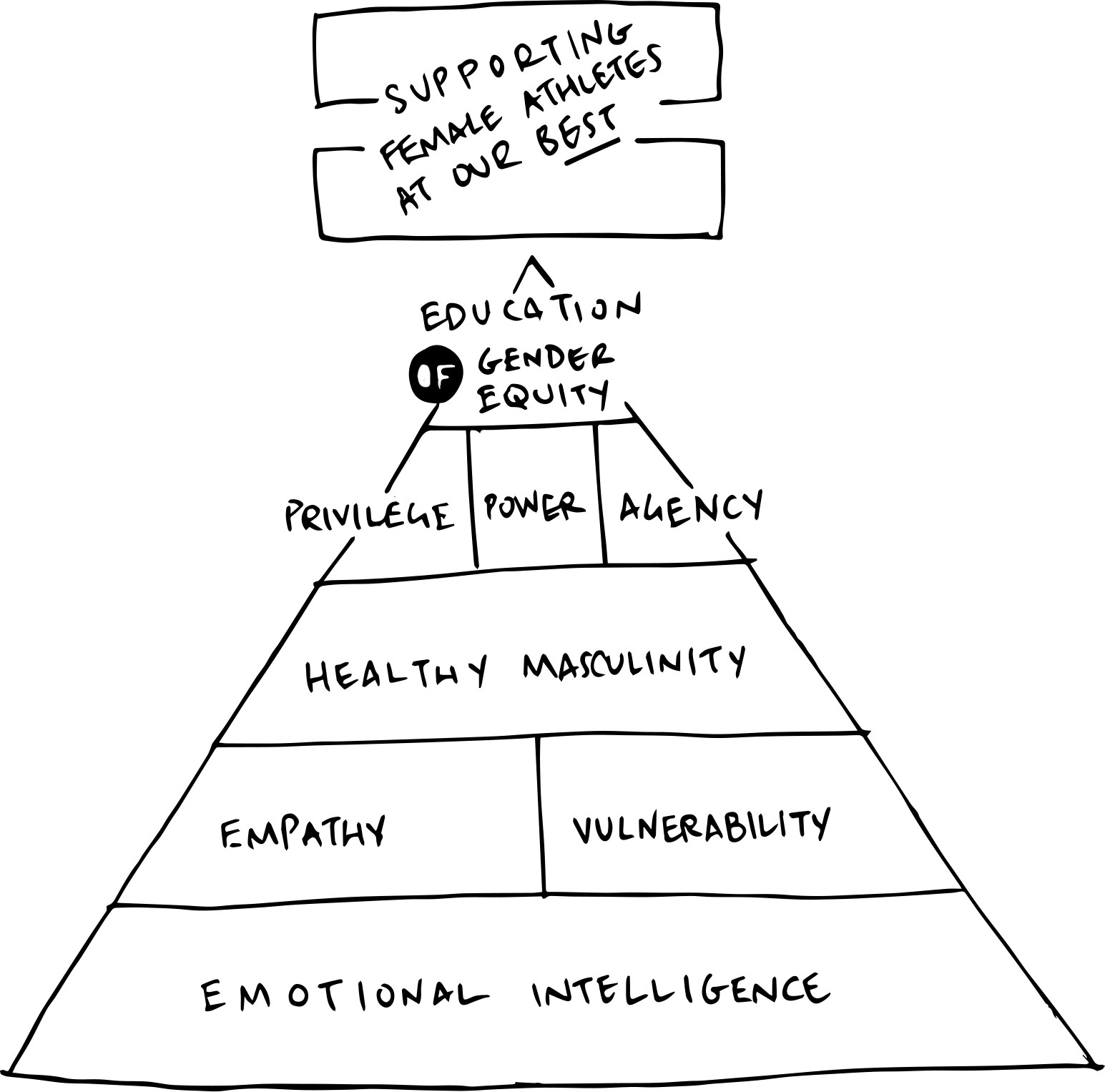

Below is a pyramid that lays out an order to how I believe we should be reshaping the foundation of our masculinity. Emotional intelligence is at the very bottom because a language and understanding needs to be created before we can move up the pyramid. It’s easier to express empathy and vulnerability if you have words to match those feelings. Once we’ve practiced and feel comfortable being vulnerable with each other, we can unpack our toxic masculinity and work on developing a healthier masculinity. We would then address our own power, privilege and agency (which is also apart of the education of gender equity) to lead us into educating ourselves. After we’ve done all of this, I believe we would be able to give female athletes our best genuine support.

Illustration by Bailey Zahniser

Lastly, I’m challenging the men speaking in the SUSO project to address some of these fundamental topics and encourage their followers to do so as well. No matter how much advocacy we do, without making the necessary changes to men’s and mixed ultimate cultures, I fear we are just perpetuating male-dominated spaces that women are invited join.

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.