Team India Open huddled around white board at national training camp.

Team India Open huddled around white board at national training camp.

Siva Kumar

Siva Kumar loves playing frisbee. He’s had a paining shoulder injury for over a year because he just won’t stop playing. He still wakes up before 5 AM every Sunday morning to walk himself to Besant Nagar beach in Chennai so he can play pick up at 5:30. Chennai is known as one of the hottest and most humid cities in India and if there is no cloud cover, it can be too hot to play on the sand by 7:30 AM. Of course, this being India, 5:30 usually turns into 5:50, so at least that’s 20 minutes less of damage he’s doing to that shoulder.

If he feels like it, and he often does, Siva can head to the beach any night of the week to play more frisbee under a street lamp at the corner of the beach where the road turns. You will find boys, and a few girls, of all ages and family backgrounds playing under that light. Welcome to the Chennai beach. It’s the breeding grounds for a lot of the frisbee talent in the country, and one of the only places in India where frisbee is played at night under lights.

Besant Nagar Beach

Access to space is very hard to come by in India. Cricket is simultaneously religion, politics and pop culture in India. Newborn boys are given a bat in the delivery room. The only time I’ve witnessed traffic cease in the country was during the India vs. Pakistan match. Check out this home video of Team India Open players reacting to three straight wickets (a hat trick) that let India beat Bangladesh.

Watch Team India Open as they come together during a final second, game-changing, instant replay is reviewed by the cricket referees.

Cricketers take over most public grounds (“fields”) by 6:30 AM, so you must show up early to set up your frisbee cones. You won’t find a single woman playing cricket on these mud grounds (“dirt fields”, called mud even when they are dry), but you can definitely find women playing ultimate. In fact, it’s one of the only places in India where you will find men and women playing together.

Chennai is the only place in the world where they play beach ultimate on a full 70 m field, 7 vs. 7. Nobody told them otherwise, they were just playing the rules they had seen on YouTube. Usually, beach ultimate is played on a small field, 5 vs. 5, it’s a much slower game than the grass version because players can’t run or jump as well on sand. For me, it felt way too big, there was just no way to cover that much sand. Siva doesn’t care about that. Nobody cares.

At the Chennai beach, there is enough space, and there is frisbee. The beach, from road to shore, is quite large. Maybe 0.5 km long and 1 km wide. Enough for a small market, a Muscle Beach weight gym, and countless beach goers. But don’t go in the water (it isn’t the healthiest for swimming—I wasn’t told why but I was told to stay away). The beach is public, so the frisbee happens out in the open. It’s a potent recruiting platform.

Murunka x2

This same beach is the subject of an award winning Sundance documentary, 175 Grams, about the effect frisbee has had on the slum neighborhood nearby. One such player, Ganesha “Murunka” Moorthi, currently plays on Team India Open. Murunka is a family nickname, it’s not from frisbee. Murunka shares the name with his grandfather. A murunka is a bumpy green rod-shaped vegetable that grows in trees and is used to make sambar (spicy stew with lentils) in South Indian food. You can’t tell, but Murunka is a dynamite tree climber. He is also a strong swimmer. He hails from a family of fisherman and he fishes the ocean with just his shorts and a net to help his family put food on the table, except there is no room for a table in his family’s modest two-room home. And he holds a second job at a dental clinic in town.

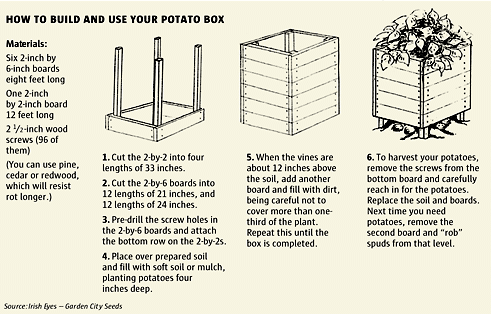

Siva runs around Team India Open training camp while screaming “potato box, potato box.” English is not his first language (that would be Tamil), and he is having enough fun to not care. We are playing a game where his team needs to defend a cone from being knocked on its side. The cones stands inside a 2m x 2m box, and Siva wants his team to “protect the box.”

A potato box.

Team India Open is unique for India: it’s completely meritocratic. Players on the team earned their spot only after national tryouts were held. Spots were awarded regardless of whether or not they are able to afford the campaign costs (which are massive, more on that later). The team is made up of players mostly from three major cities: Chennai, Bangalore, and Bombay. The cities are distinct. One has a traditional mindset (the old seat of the British empire), one is a booming tech hub, and one is the most populated city in India known for its inhumanly sweaty train rides.

Murunka and Siva Raman embrace in London in 2015.

Team India Open

Team India Open is the second all-male team that will represent India internationally at a proper grass ultimate tournament (an all-male team played at Asia Oceanic Ultimate Championships 2015 in Hong Kong). Indian club teams are all co-ed to guarantee that teams can include women due to a low total number of Indian female players, and the fact that an all-women’s team might be bullied in India. It is very uncommon to see a group of women alone playing sports. Likely, male cricketers would kick them off the fields.

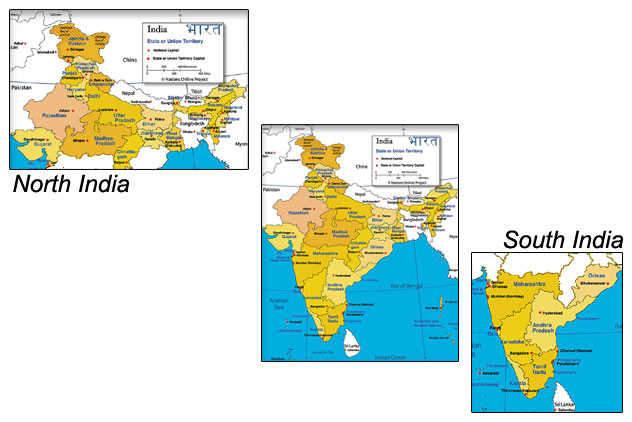

Our team is made up of players mostly from 3 major cities: Chennai (where they speak Tamil), Bangalore (Kannada), and Bombay (Hindi). This is common for an Indian team. The country itself is loosely divided into North and South. The North is known for the Taj Mahal, Naan bread, the Himalayas, and spicy food. The South is known for its many languages, flowers in women’s hair, dosas and idlis. India has 22 official languages. The country is made of 29 different states. Each state is full of local languages (beyond the official ones), cultures, and food. Imagine if you moved from Colorado to Washington (like I did), and you had to learn a new language. It happens in India. Yes, English is most people’s second language, but the diversity in Indian ultimate is massive compared to American ultimate which is made up mostly of college educated white men.

North and South India, and the states of India

National (all-star) teams all face similar challenges: having to re-build team chemistry from scratch, players filling different roles than they had on their home teams, clashing egos. In India, we have the added challenge of language. Direct translation is not so bad. The team speaks mostly 3 languages (Tamil, Hindi, and English), yet most of us have decent English (some players have much gooder English than I). We have a few all-stars that speak three and even four languages. We use “whisper” translation, where one person speaks in the front of the group and translators are strategically seated throughout the crowd so they can whisper along. We are slowly coming up with common vocabulary (typically in English, lucky for me). Potato box.

The difficulties come when players need to interact quickly on the field or when players want to take a break from translation at lunch and rest. In Bangalore, we can play almost until noon when it reaches 95 F or more. The team loses cohesion in these moments. The groups clumps into the three cities. We know it’s a problem. Or imagine us having a team discussion on team values, the feelings that we think are important to our campaign (like unity, pride, spirit), speakers explaining their feelings in a second or third language.

Our team is not, though, the first meritocratic team. Last year, there was a co-ed team that attended the U23 World Championships in London. This team also faced issues. For example, they struggled getting themselves to London. Indian visa applications are highly scrutinized by the UK, as Indians are perceived as potential immigrants. It is difficult to persuade the UK that Indian citizens promise to return to India after a trip to the UK, not to mention the notorious bureaucracy of India’s government. The U23 team had players that didn’t have their own birth certificate, not to mention a passport, at the beginning of the campaign. They didn’t understand the concept of a visa. “What do you mean someone has to sign a piece of paper that says I’m allowed to go somewhere?”

India U23 Team at 2015 Worlds.

A big part of getting visas is having a pile of funds ready to go to prove that the trip is legitimate. For meritocratic teams, this includes a ton of fundraising. The U23 campaign has an incredible story that cannot be done justice in this article. Luckily, there is a talented documentary filmmaker named Varsha Yeshwant Kumar who lives in Bangalore and captured the entire thing. The climax begins with the entire team being denied visas and having to cancel their plane flights (without refund) with a few weeks until the tournament. It ends with an angel investor and everybody on the team crying, hugging, yelling, and dancing (in typical Bollywood fashion) in the British embassy in Chennai.

There may be no angel investor for Team India Open. A year ago, India sent just one U23 team abroad and this year, India is sending five (Open, Women, Mixed, Masters, and U19 Open). I’m so humbled that we stay motivated with this elephant in the room. Note that I am used to very different playing conditions. My background is one of a privileged straight white male from the US who picked up ultimate at university and played club and professionally (mostly on the West Coast). I’m glad I can use this platform to introduce this team to the frisbee world.

Maybe it’s blind optimism, but we still wake up by 5AM to make it to national training camps. We still hold these national training camps on mud grounds because they are available (actually one of our reservations for playing grounds was cancelled at the last minute and our incredible Team Manager Abhishek “Cisa” Srinivas found some new grounds in only days, quite the feat). We still sit on non-A/C trains for hours at a time to travel around India to training camps. This feels typical for this team, this is what they know. I don’t mean to raise pity, just to show that ultimate can overshadow all this.

Coaching India

I’m trying to be careful with my words as I write here. Nothing about Indian ultimate or Indian culture is bad. Nothing about American culture is bad. Both countries define happiness and success in different ways. The fact that I listed happiness and success as two separate things already says something about me. No judgement, just noting the differences (not to mention that fact that many different cultures exist within the US, and within India). I believe that that this should be an Indian team, I want little say in team decision making. Given this, some interesting problems arise.

Power dynamics (between players and a coach or between students and a teacher) are a little different in India. The gap between the two is wider. In schools, students are more submissive. Getting called on to speak in class can be an embarrassing moment rather than a learning moment. Right answers will match the textbook verbatim, word for word. Wrong answers are anything that varies from that. I see it at training camp. In a huddle, players are very timid to speak, especially the younger players. Age plays a role in Indian power dynamics as well. Among groups of young people, older girls are referred to as Didi or Akka, older boys as Bhaiyya or Anna. Both mean “older sister” or “older brother” in Hindi or Tamil. This custom exists across most of India’s cultures. Matty Bhaiyya might explain an offensive concept and ask if anybody has any questions. Nobody does.

Team India Open

Value systems are different everywhere. I hope to carry professionalism with me everywhere I go. Punctuality, staying in good contact by email or by phone, or coming to frisbee practice prepared with water and food are things I’ve tried to maintain through my frisbee career. Players here may be coming straight from work, may not have eaten at all before practice, and may be transferring busses just to make it to practice (not the most reliable transportation). Even if they don’t have the means to, and even if they know in their heart that they won’t be able to, if you ask for them to show up on time or bring something to practice they’ll say “yes”. Is it weakness to say “no” to a white authority figure that speaks good English? I’m trying to find balance between getting mad at people for being late (correcting their “poor” behavior), and learning a different way of life.

I’m an outsider, an observer, and I like this role in part because I’m not affecting the Indian-ness of the team. Am I less a part of the team because of this? Maybe. But I’ve also seen that my voice carries extra weight. Maybe it’s the fact that I have a long frisbee pedigree, or maybe it’s the color of my skin, but I get uncomfortable when I see my voice dominating conversation. Still, when the team brought me here, they told me it was to bring a new perspective on ultimate. As I get darker from the sun, these problems will hopefully lighten. Wish us luck. Potato box!

Comments Policy: At Skyd, we value all legitimate contributions to the discussion of ultimate. However, please ensure your input is respectful. Hateful, slanderous, or disrespectful comments will be deleted. For grammatical, factual, and typographic errors, instead of leaving a comment, please e-mail our editors directly at editors [at] skydmagazine.com.